SB Tweet Digest #3 (april 2010) . [1/2]

may 02, 2010.

Last month the SoundBlog

twitter birdie ![]() yelped 26 times. Here's some of the things that it was on about (first of two digest posts):

yelped 26 times. Here's some of the things that it was on about (first of two digest posts):

...

[11865813045]

I was intrigued by the 'urban parasites', created by the Mexican artist

Gilberto Esparza, that I read about on Régine

Debatty's WMMNA. Gilberto and his team construct

simple but ingenuous robots, mainly from scrap metal and other discarded

stuff

that they collect at junkyards. These 'robo-toys' are then set loose

in the city, where the creatures look for free energy to feed on,

in order to 'survive'. The dblt (which stands for diablito:

imp) moves along the power cables spanning the streets, feeding on its electricity.

Meanwhile, diablito records and stores sounds from its environment,

which every now and then - depending on its mood - it plays back again ("Esta

especie almacena sonidos de su entorno y los reproduce intermitentemente

según su estado de ánimo." Which, you will agree, is an accurate

definition of what is a phonographer.) You can see

the imp in action in this short

clip on the Parásitor Urbanos website. Besides being in spanish,

much of the interesting content of that website is hidden behind a Flash-intro;

if you'd like to explore some more visuals of Gilberto's work, better go

directly to his proceso-page.

simple but ingenuous robots, mainly from scrap metal and other discarded

stuff

that they collect at junkyards. These 'robo-toys' are then set loose

in the city, where the creatures look for free energy to feed on,

in order to 'survive'. The dblt (which stands for diablito:

imp) moves along the power cables spanning the streets, feeding on its electricity.

Meanwhile, diablito records and stores sounds from its environment,

which every now and then - depending on its mood - it plays back again ("Esta

especie almacena sonidos de su entorno y los reproduce intermitentemente

según su estado de ánimo." Which, you will agree, is an accurate

definition of what is a phonographer.) You can see

the imp in action in this short

clip on the Parásitor Urbanos website. Besides being in spanish,

much of the interesting content of that website is hidden behind a Flash-intro;

if you'd like to explore some more visuals of Gilberto's work, better go

directly to his proceso-page.

Is it because of my current reading of Steve Goodman's Sonic

Warfare

that I imagined this diablito evolving into a high-tech automatized

spy-machine rather than an eco-woolen clad urban soundscape collector?

On

the other hand, maybe some of its descendants will mutate into

tape-o-bugs

... Now that would be awesome.

|

|

[12326992440]

Digital Folklore

is another book that I recently read. Edited by Olia

Lialina and Dragan

Espenscheid, designed by Manuel

Bürger. The design is an essential ingredient of the book, parts of which

are about how websites used to look.

(Not only the browsers, also our screens were different

back then; and so were the machines to which they were attached and the

manner in which in turn the machine were hooked onto the web. In a user's

experience of websites and the internet, all of this is intimately

connected. Whence there is in fact no possible way to truly 'relive'

the feel of the web of the past within that of today, using today's browsers,

today's laptops and today's connections. [...] What is equally remarkable, is that these

remarks sound as if I am considering a span of ages here, while it is actually

no more than some 15 years.)

The Digital Folklore Reader takes you back to the days

when much of the web, if not all of it, was a vernacular web, where

users (which is the Reader's main key-word) welcomed one another on their personal homepages, adorned with free animated gifs

a prominent and inviting mail me link and a short text set in Comic Sans, all put against

a colorful and repeating, maybe even blinking, background, and with MIDI versions of popular tunes to set the tone and please the ear.

Indeed, they are much like this Rina's

Page, that more than 10 years ago (in 1999), for some reason I decided

to save for posterity (at least temporarily).

Over that decade, the editors observe, the web

has become a far more 'developed and highly regulated space', where old fashioned homepages like

Rina's have become

obsolete.

Of course.

Rina'll be on Facebook now. ( * )

Her

former homepage not only looks resplendently 'old school'. It is also

very much out of place within the Google's Chrome browser that speads across the wide screen

of my MacBook. Rina's site was a part of the early

IE and Netscape 4 web, supposed

to be dripping slowly onto the bulky but smallish square tube-screen of a PowerPC via a busily blinking

telephone modem ... That is why this paper book is able

to tell the story and bring across the feel of that 'bright, rich, personal, slow and under

construction' web so much better than a website could, with a set of

're-built' old school pages, rendered at hi-speed in one of today's fast

and standards compliant browsers.

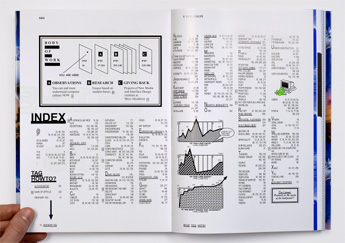

Digital Folklore has three sections: an 'Observations' part (with texts on the 'vernacular web' (that I remembered having read before, online), on - up and coming - 'the cloud', ancient attempts at a 3D web with VRML, fonts, the computer ...), a 'Research' part (papers written by the editors' students) and 'Giving Back' (succinct, and glossy, presentations of a handful of projects of new media and interface design students at Merz Akademie).

Digital

Folklore is a playful yet serious ode to the swarm of early web users,

the amateurs who - it is the authors' solemn conviction - while diligently

hacking out the simplest of HTML

code to built personal home pages, cat sites, hobby sites and

webrings, both were and made the web, until, somewhere

in the mid/end 1990's, with dazzling speed it set out

to commercialize. The management of its exponentially growing content was

confided to database systems and a new caste of professionals took over

its design and coding.

Digital

Folklore is a playful yet serious ode to the swarm of early web users,

the amateurs who - it is the authors' solemn conviction - while diligently

hacking out the simplest of HTML

code to built personal home pages, cat sites, hobby sites and

webrings, both were and made the web, until, somewhere

in the mid/end 1990's, with dazzling speed it set out

to commercialize. The management of its exponentially growing content was

confided to database systems and a new caste of professionals took over

its design and coding.

Digital Folklore tells (and shows) a certain history of a certain web in a certain way, that to many of its early active users will feel pretty familiar. A story that would be easy to dismiss as the smallest among footnotes to the one that's set in bold face, of a web that because of its in-near-to-no-time rise to the status of the most massive of mass media, became the battlefield for an ongoing power struggle between meta/mega-sized corporations and institutions.

The nostalgia lurking behind many of Digital

Folklore's pages is not easy to avoid. The book had me ponder my personal online history.

I recalled some of the sites and services that I frequented, but that since

have perished (most notably one of the first examples of a 'social network

site', sixdegrees.com,

and the 'independent online music network', mp3.com).

It made me think of the many successive

and drastic

metamorphoses that for years in a stretch many websites continued to

undergo, as did my own. ( ** )

It had me dive deep into my archives to find the

very first webpages that I made, some fifteen years ago, when we surfed on Mosaic.

Those pages did survive. But not online. They

only survived because, at the time, I printed them. On ordinary

paper. I tried to unearth them with archive.org's

WayBackMachine, but I guess they are way too back

( *** ).

The printed versions allowed me to re-construct

them.

(It was very easy in fact to find back exactly the same clip-art images online

that I used originally (the little saxophone, the blue arrow, and the 'under

construction' sign). That particular part of digital

folklore - apparently - remains thoroughly rooted, also in today's web.)

On today's web users no longer copy and paste lines of HTML

and then publish their homepages. They compose profiles (give

away all their personal data) and (for free) hand over all sorts of (original and/or

'borrowed') content

to a handful of commercial mega-platforms,

for which rather than the users and the content they donate,

the establishment, consolidation and growth of the power of

the platform in and by itself is the foremost issue that is at stake, a power that is solely based

on the potential (future) economic value of the platform's database with user-provided

information.

I don't know whether that is good or whether that is bad.

Or, I actually do know that it is bad, but that is another

story altogether. It does not mean though, that I miss the long gone days of

animated 'mail me' gifs, glittering backgrounds and 'under construction'

signs. And it will also be very, very unlikely that

Rina and the millions of other former 'Welcome to my Homepage'

makers, would dump their Facebook account and switch their homepage back online, were they given the choice.

They may have sold their souls in the process, but doesn't Facebook deliver

what they've been asking for: visitors, attention, contacts?

Meanwhile content comes and content goes. It washes on and off our screens like

the water of the oceans washes on and off our shores. Funny, really, that apparently though it is not

the web itself that is the medium best suited to tell some of the (hi)stories related to

all of that content and the forms in which it was presented.

Books do that much better.

Digital Folklore

is a fine example.

(Easiest get will be to order it online

...)

[ Digital Folklore. To computer users, with love and respect. Olia Lialina, Dragan Espenschied (ed.) Merz & Solitude, 2009. 288p. ISBN: 9 783937 982255 ]

|

|

|

|

[12167958658]

Last month Moritz Ebinger's Radio

Rood (Radio Red) continued its live broadcasts, on three successive wednesdays from

inside the library of the FBKVB (the Netherlands Foundation for Visual Arts, Design

and Architecture) on the Amsterdam Brouwersgracht. Broadcasts, in the course

of which a long parade of more or less colorful guests shone their light on

all possible facets of ... red ... : red

in general, but also more in particular: red.

Above there's a couple of red radio photographs. In the one in the lower left corner you see

Heinz Hermann Polzer, better known - at least for the Dutch viewers - as

Drs. P, who, surprisingly (or maybe not), was an undisputed highlight in this

series of "red" broadcasts.

[12243530905]

On his

High Ponytail blog Maready posted an - as always, nice and

thoughtful - entry on a 2003 Jandek

album, "The Gone Wait". That was good enough reason for me to spend some

time discovering this "outsider musician", whose name I saw regularly mentioned, who

seemed to intrigue a great many, but whose music I had never

heard. This changed with Maready's post. Indeed, I heard an

awful lot of Jandek these past two weeks (and little else besides). Thirty

(30) full albums, to be precise, some days played back at random, other

days in their order of release. From the very first one (Corwood Industries

0739 - Ready for the House) up to the 29th (Corwood Industries

0767 - Put My Dream On This Planet). Then there's a little jump

to the 35th: The Gone Wait.  Together

that's is about half of the complete oeuvre that Jandek steadily has been

building since the late 1970s, released as a still ongoing stream of self-edited

records, available by mail-order from (always the same) P.O. Box address somewhere

in Houston, Texas. Highly recommended, actually. Not so much for its

originality (none of it is terribly original in the sense of 'not

having heard anything like it before'), as for its stubborness, an obvious obsessiveness, its

coherence and consistency. And the

man's untiring persistence in constructing something so ... monumental

is the word, really. Most of time it is just him, singing (or rather 'chanting')

and strumming a guitar, that is not so much un- as that it is open-tuned.

Jandek sometimes sounds like a raving Dylan. And some of his stuff sounds

as if recorded by an overly introvert Beefheart and his Magic Band. He often

has a habit of __s t r e t c h__-ing

the words that he's uttering. Some are unaccompanied vocal recordings, a capella. On others Jandek

plays the piano. Or (on "The Gone Wait") he uses a fretless electric bass instead of a guitar. Sometimes other instruments join in, sometimes

there's also others playing along, though it certainly not always is the case

that other or more instruments mean that there is also others performing

in the recordings. Despite the changes occurring over time, from record to record,

together the 30 album

sound as if were but one, with - as far as I am concerned - rarely a dull moment.

Together

that's is about half of the complete oeuvre that Jandek steadily has been

building since the late 1970s, released as a still ongoing stream of self-edited

records, available by mail-order from (always the same) P.O. Box address somewhere

in Houston, Texas. Highly recommended, actually. Not so much for its

originality (none of it is terribly original in the sense of 'not

having heard anything like it before'), as for its stubborness, an obvious obsessiveness, its

coherence and consistency. And the

man's untiring persistence in constructing something so ... monumental

is the word, really. Most of time it is just him, singing (or rather 'chanting')

and strumming a guitar, that is not so much un- as that it is open-tuned.

Jandek sometimes sounds like a raving Dylan. And some of his stuff sounds

as if recorded by an overly introvert Beefheart and his Magic Band. He often

has a habit of __s t r e t c h__-ing

the words that he's uttering. Some are unaccompanied vocal recordings, a capella. On others Jandek

plays the piano. Or (on "The Gone Wait") he uses a fretless electric bass instead of a guitar. Sometimes other instruments join in, sometimes

there's also others playing along, though it certainly not always is the case

that other or more instruments mean that there is also others performing

in the recordings. Despite the changes occurring over time, from record to record,

together the 30 album

sound as if were but one, with - as far as I am concerned - rarely a dull moment.

Much looking forward now to getting to know also the remaining 30.

Who or whatever Jandek may be, the man is surely not a dilettante.

[ All Jandeks, including those originally released on vinyl, remain available as CDs and can be ordered by sending mail (and payment) to the Houston post-office box; each title costs a mere $8,== ]

- pt 2 : Jason Freeman's Piano

Etudes

&

Amsterdam Music Hack Day -

...

! Follow @soundblog

_( ![]() )_ iokoo@ wolloF

!

)_ iokoo@ wolloF

!

notes __ ::

(*) Rina's homepage used to be hosted

by infoseek.com. The original url was

http://homepages.infoseek.com/~smilestheultimatechattingmachine/

[ ^ ]

(**) In this sense the web did 'converge'. Nowadays drastic make-overs of

complete web sites, which until the early 2000s were not unusual, nowadays are far more seldom.

Sites continue to evolve, but do no longer change their 'looks' every six months or so.

Most of them did arrive at

some sort of

optimum model for the presentation of their content. And then stick to it.

[ ^ ]

(***) Archive.org does an admirable job.

It has happened quite a few time that I managed to find back content on some site or other that no

longer was part of the site's current version, but that was available using the archive's 'timemachine'.

Generally speaking though, the attempt at archiving all of the web's past and future content in

an ongoing series of successive snapshots,

cannot be but Don Quixotean.

[ ^ ]

tags: twitter, digest

# .360.

smub.it | del.icio.us | Digg it! | reddit | StumbleUpon

comments for Tweet Digest #3 (april 2010) . [1/2] ::

|

Comments are disabled |