On Wednesday May 8th, 2019, the first day of a three day /business/field/ trip to Amsterdam with an international group of IESA MPAE (MBA in Performing Arts, Entertainment and Cultural Industries Management) students, we visited STEIM (STudio for Electro-Instrumental Music), an important and influential independent electronic music center founded in 1969 by a group of young Dutch composers (Misha Mengelberg, Louis Andriessen, Peter Schat, Dick Raaymakers, Jan van Vlijmen, Reinbert de Leeuw, Konrad Boehmer) that at the time fought for the reformation of Amsterdam's feudal music structures, most notably by causing a public scandal when they disrupted a performance of the Concertgebouw Orchestra by making a lot of noise. From 1981 until his untimely death in 2008, the STEIM center was led by performer, improviser, inventor and live-electronic-music pioneer Michel Waisvisz. STEIM initially focused on developing tools for experimental electronic musicians for live stage performance art, and still carries the 'touch philosophy' as its motto: "Touch is crucial in communicating with the new electronic performance art technologies".

We met with STEIM's current artistic director, Dick Rijken, at STEIM's current location [[tweet]], part of a suburban 'breeding space', the Urban resort Lely in a former school building at Schipluidenlaan 12 in the Slotervaart neighbourhood, south of Amsterdam's city centre.

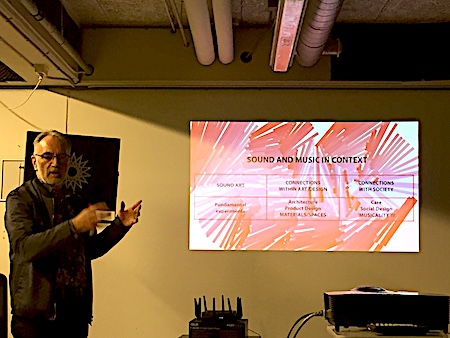

The following is a complete, unabridged and very literal transcription of the sound recording that I made of Dick's presentation and the discussion, for use by students as reference and lecture notes.

SoundBlog PAPAM entries:

(2020, november 10) - Zingaro, equestrian theatre (papam18_5)

(2019, december 22) - Rendez-vous Contemporains de Saint-Merry (papam19_2)

(2019, october 11) - STEIM, Amsterdam (papam19_1)

(2018, may 05) - La Gaîté Lyrique (papam18-4)

(2018, april 30) - IRCAM (papam18-3)

(2018, april 20) - Sonic Protest Festival (papam18-2)

(2018, april 10) - La Générale Nord_Est (papam18-1)

SoundBlog entries around and about STEIM:

(2019, october 11) - STEIM, Amsterdam (PAMP19_1)

(2012, june 24) - Ninja Fruit Plus Instruments

(2008, july 28) - Michel's Song of Praise

(2008, june 20) - Michel Waisvisz (1949-2008)

52 min read 🤓

STEIM, Amsterdam (papam19_1)

ocotober 11, 2019

"The End Of Music As We Know It"

[dr] "You're in a course on art and cultural management, right?"

[st1] "But very focused on performing arts, so music, theatre, cinema... circus..."

[dr] "There's a difference, whether I talk about the core of the artistic ideas or the way..."

[st1] "Both!"

[dr] "I'll tell you a little bit about the history. It's a long history. STEIM is fifty years old, this year. We were founded in 1969. The initial idea at the time —and it's kind of interesting so let me talk a little bit about that— you have to sort of think back fifty years, or even more... At some point in the 20th century there was technology that could produce sound. For us, these days, that's quite normal, but you have to realise, it was for the first time in history, in the early 20th century, that sound didn't come from anything. Literally: any THING. There was no THING producing the sound. People discovered machines producing sine waves or other wave forms, machines that you then could connect to an amplifier with a speaker, and suddenly there was a sound in the space that didn't come from any THING. This was, you know, utterly fascinating, to many composers. And ... in the beginning ... and, you know, of course ... most composers and musicians are interested in sound, and everybody made a big thing about the sound of their instrument, and people spent a lot of money to get their instruments to sound better ... so this new sonic world that was opening up, was very, very fascinating to people.

It was also however, extremely difficult to work with. It is one thing to have a speaker producing some kind of wave, it's another thing to control that sound. Like, you know, 90 percent of playing an instrument is all about how you control whatever the instrument is capable of doing. People spend years and years, their whole lives, trying to control the sounds that they can make with their guitar, with their piano ... And I don't know if you realise it, but in the early days of electronic music, if you wanted to work with sound, literally the only thing you could do is record it on a piece of tape, physical tape, and splice it with a razor blade ... and then copy and paste, but literally with a meter of tape.

Stuff like that.

Which was of course a lot of work. Very, very cumbersome. And out of that, out of frustration, or maybe I should not say frustration, but, out of this curiosity: how do we control this sonic world, the way we control our instruments ? ... with our hands, with our bodies ... rather than, you know, with a razor blade. That's all very ... indirect, if you know what I mean. And composers were then in a better spot, in the mid 20th century, than musicians, who just had no place in this world. If there were concerts where you had, like electronic music and real performance, the electronic music would be a tape, you know, that was playing, and the performers had to deal with the tape.

The word STEIM comes from STudio for Electro-Instrumental Music.

So all of our history has really been about this question: how do you PLAY this sonic world? Lets look at the instrumental side more than to look at the more conceptual and compositional side. So then there was a group of composers who together said: 'We need a place, that does this, that does these experiments!' ... So the whole idea of the relationship between the body and sound, that always has been very important to STEIM, because, you know, performing arts are really physical in nature. Dance is very physical, musical performances are physical... It's a little bit ironic in the sense that... in the old days if you went, like I said, if you went to an electronic concert, if it was with performers, you would at least have someone performing; but I have literally been to concerts, still in the 1980s, when I studied at the Institute for Sonology, I went to concerts where there was basically a guy on the first row, who at some point would like, if everybody was seated, and then he would like turn on ... press play on a tape recorder ... [students laughing] ... and sit down. And we would just like, you know, close our eyes and listen to the music. But of course that's a weird concept for a live performance. "

[st1] "It is often still today like this, at electronic music concerts."

[dr] "That's what I want to say. The irony of the situation is, we still have many performances that..."

[st2] "You can look at someone doing things."

[st3] "Staring at a screen..."

|

Musical jugglers: Tom Johnson, Gandini & STEIM

[dr] "That's exactly the point I wanted to make, the irony of the situation, if someone is doing something with a laptop, they might be, you know, checking their email while playing a sound file, you know. So this is always been a big thing in the history of STEIM. We want to see you perform, we want to see the beauty of that, the way it is beautiful to watch, you know, somebody getting involved with their entire body in a violin, not just the two arms, but everything. For any instrumentalist, the theatrical part of the performance is the engagement of the entire body. So we've done a lot of that. Michel Waisvisz was our artistic director for a long time, maybe for thirty years, I am not quite sure when Michel started ( * ), but he died in 2008, and that's when I took over.

Anyone ever heard of the composer Tom Johnson?"

[hs] "Tom lives in Paris, not far from La Générale, actually... His 75th birthday celebration concert was at La Générale, in 2015."

[dr] "Tom is a very formal minimal composer. He typically writes pieces that... you know, basically, he picks four notes and he gives you every possible combination of these four notes. It's very minimalistic, it's very repetitive, it's very, you know, hypnotising."

[st2] "It is mathematical."

[dr] "Yes, it's very mathematical, he is known for his mathematic approach to composing. And at some point he came to us, some years ago, I think it was 2011, saying that he had written a piece that was literally called Three notes for three jugglers.

...

Have a look, it's an amazing clip."

[dr] "He was already working with these jugglers, from London, called the Gandini's. And he had a score, twenty minutes long. And he asked STEIM whether we could make juggling balls that make a sound when you throw them, or catch them. That took a bit of research, but we managed to do it. And the theatrical heart of the performance is the jugglers' engagement of their entire body.

The speakers are in the balls, so there's no extra stuff. I don't know what you know about juggling. I didn't know much about juggling when these guys came to us... You have to realise that the amount of time that the ball is in the air depends on how high you throw it. And then there's three guys (... there's also a woman, but she's not in this piece...) look at how incredibly synchronised they are! These guys are so good, it's just unbelievable. And every once in a while you'll see one of them throwing one of the balls a little bit higher, and then after that you'll hear a different kind of musical pattern... If you look at the whole twenty minutes, it's like Kraftwerk with juggling! It's utterly fascinating. And of course they don't have a score, they can't look at something else. I don't know if you noticed but they vaguely look at the highest spot where there ball has to go, they know exactly how high they need to throw a ball, so they're sort of looking there and you will see all the balls, like, making this arc. And sometimes the guy at the left would be throwing higher balls, and he would be looking like this... [makes a look like the guy at the left]

But everything their hands do.

They make it look so easy. I tried it and I'm really bad at it. So for me this is a perfect example of this physicality, it's the body doing its work. Ninety percent of it is intuitive and nothing else. So this is what became of that tradition, this whole idea of how do you play sounds? Well, this is an interesting example. And over the years... in the eighties there was the development of the so called MIDI standard, the Musical Instrument Digital Interface. That was the first time that you could basically send digital commands to synthesizers and other sound producing modules, you know, and control them, even if the synthesizers themselves were often still analogue, you could at least, you know, have things like presets. We are still experimenting with analogue electronics, but, you know, if you have a really complicated set-up and you finish a song or a piece, and then you have to play the next piece, it could take five or ten minutes to sort of to re-patch things so, you know, it's a lot of work. And so: presets! Good idea! And then in the nineties came the samplers and everything became more digital even at the deepest level of music production. And that's when STEIM started experimenting with sensors, basically. This old idea of, let's have the body involved in making music. What about the body, or what about movements or gestures, can we sense in the digital world? And then how do you translate it into sound? And that was basically when STEIM became, I think you can almost say, 'world famous'. We were one of the only places in the world where you could literally experiment with ... crazy sensors.

Interactions, fingers, screens, design

At the time, in the nineties, I was running a degree at the Utrecht school of the Arts, which was called 'Interaction Design', teaching students, you know, interface design and those kind of things. But STEIM was for us... they had this that was called the Sensorlab, it was a box, basically, you could hook up analog sensors, you know, movement sensors, light sensors, relatively cheap to build, and it would, you know, basically give you MIDI, which was extremely unique at the time, you couldn't just buy that kind of stuff. These days you buy an Arduino board for -, way, twenty euros, and you can do it. But at that time STEIM was really unique. Artists from all over the world would come to Amsterdam and basically do their thing here, for a year, working within this premise of physical instrumentality. 'Touch' was the keyword, it was all touching, touching sound... So that was when Michel was at its heyday... But even then, for me, it was so awesome, because also the field of interface design and interaction design is a bit of a sterile field if you only at screens with menus on them and, you know, the only thing you do is click on a mouse...

I can remember we had one brilliant student at the time —and it was very closely related to this kind of stuff, it was fascinating— he was completely fascinated by the way objects move on the screen, how fast they move, and so at some point ... this was in 19... even before the world wide web, so in 1992 or 1993... you would have a screen with three buttons on it, three times the same button, with different animations. So one button was like... on or off... you took your mouse to the image of the button, you pressed it and you would see it in and then jump out, like very discrete. And he had one that sort of, it had basically eight steps of animation... you would see the button go in and then go out. And then he had the third one, it was the same one as the second one, but it was mmuucchh sslloowweerr... And the weird thing is, they felt differently to your finger. It was the same mouse button. The mouse only says, you know, 'click'. But because of the different information you get through you eyes, it literally... The third one felt heavy! It was so weird! At that time, you know, all of us realised that "Wow, this is... this is absolutely fascinating!" And everybody, everybody liked the second one best because this was about the speed, the normal speed at which people move their hands. The first one was blunt, the third one was too... slow. If anyone has an iPhone... the keyboard on that iPhone was designed by that student. He did end up at Apple, they really loved his work, after he graduated. He doesn't work there anymore because he was getting tired of all the lawsuits. I don't know if you hear about the lawsuits. Samsung and Apple, Samsung stealing... these were all his ideas they were constantly stealing."

[st3] "So he just went to Samsung..."

[all laughing]

[dr] "No, no, no... He did not go yo Samsung [laughs]. But he was getting tired, he said 'I'm spending way too much time in court rooms in Washington instead of creating new...' Again, it was this weird physicality of something that wasn't visible...

So if we then fast-forward to when I took over, in 2008, that was a strange moment in time because all those things that STEIM had been known for and had been unique for, for a long time, had been... so which put us in a strange position. As I said, the technology now costs 5 or 10 or 20 or 30 euros, depending on how fancy you want to make it... but I was faced with a laboratory that on the one hand was world famous, but that was doing things that... You know, especially nowadays every university has a music technology department.

For me as a director that was tough position to be in. A, being next to a guy that was world famous and who had done amazing things, but whose concept was sort of at the ends of its, you know... livelihood, you know what I mean to say. And at the same time, and this is where it also gets interesting, and also where management and artistic content kind of overlap and... emerge... From my history in new media I had become a professor at The Hague university in the field what was called IT and Society, so which was kind of a much broader kind of issue... You know, what does information technology mean for us as a society, for our public systems and, you know, for, for, for our care systems, out educational systems, which was like a very large grand perspective, and the university in The Hague is one of those... it's like a polytechnic school, with a lot of vocational education, so we train professionals. Nurses, accountants, you know, IT programmers ...

A concept that has always guided my thinking was this whole idea of the network society. It is radically different in many ways, you know, the idea that basically there is a big difference in... the industrial model, especially if, you know, you look at art, the industrial model of art is in a way based on the organisational model of the church - I'ma gonna take on a bit of a big history tour now... At some point, you know, Truth was given to us by God. That was the position of religions. Then Science came along, and Science said 'No,no,no,no! Truth is in the world, we need to discover it. It is our holy task as scientists to discover the Truth in the world.' The laws of nature... you get concepts like that. And then after the scientific revolution, people like Galileo who first used, you know, —again!— instruments that made him see different things. Microscopes and telescopes that made him see a world that was bigger than ours and a world that was smaller than ours. Which made us think. And we began to re-think the whole idea of Truth. And then the romantic movement came along, and says 'Well no, what a minute, there is more than just... eh... just thinking and rationality! People have intuitions, people have emotions, people feel that they are rooted in their history, of their family, of the village where they were born, they have a connection to the village where they were born.' ..."

Rovaniemi

"I don't know if someone of you has ever heard of the village called Rovaniemi, in Finland? It's a fascinating town. I always use it as an example, and Finnish people don't care if you make jokes about them, so... Rovaniemi is above the polar circle. It is really, really, really cold there. And for half the year it is dark. And then the next half year it is light. They don't have days and nights like we do. So basically, at some point in the fall the light goes out, for half a year. And everybody gets depressed and drunk and, you know... it's the high tide of suicide... And then the light goes on again. But guess what? You know Finland is the land of the thousand lakes... mosquitoes everywhere. So you do get sun, but it is unbearable outside because there are millions and millions of mosquitoes. Then it takes the entire summer, until the first night when it freezes, then all the mosquitoes are dead. And the you have about two weeks of sunlight before the light goes out again. You think: 'Guys!', you know, 'Move! Go live somewhere else! It doensn't have to be so hard!' That's always what I'm thinking: 'What a terrible life!' And yet, you know, people from Rovaniemi love the place!

It's this irrational connection you have to where you were born. We all know this, you know. And it makes, often it makes no sense. So that's the Romantic Movement. They came along. And then in the beginning... and then we get the Industrial Revolution, which kind of takes all the scientific ideas from the scientific revolution from the enlightenment, and builds this whole concept of... production... of... whatever you can think of. And we start mass producing everything. But still, in the beginning of the twentieth century we made a big deal of, like replacing a religion with a more secular idea of... you know, we basically replaced the Divine —the connection with, you know, some deity— with the Sublime —a very important concept from the Romantic Movement.

Does everybody know what the Sublime concept is? ...—:Awesome! Something is so Big, so Overwhelming that it ... [inhales, very long and deeply] ... There is a strong sense of beauty but also, you know, it's a little bit intimidating. And so basically what happens in the art sector is that it basically copies the church. It has, you know, museums instead of churches, there is artists, you know, instead of reverends and priests and everything. And it still has this idea of, you know, everything good comes from above. And so, Karl Marx coined the term of 'the avant-garde'. A French word. You have to be avant la garde, so before the troops. The intellectual elite has to show us the way, also the common people. And we literally had Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill writing operas that were performed for workers. So that they could learn what life was all about at a deeper level. I am not downplaying, you know, the artistic importance of those works. But that was the model, you know: 'Everything Good comes from Above'. And then you get people like Hegel who say, who introduce concepts like Bildung. I don't know if you know the Bildung concept, you know, it's like, personal development, connected to social development and historical development, you know, it's a nice amalgam of romantic ideas and enlightenment ideas. And then we do things like, you know, we found museums and libraries and schools. It's another thing you have to realise, you know. The idea to send every kid to school is an enormous revolution, at the beginning of the twentieth century. All western culture said, you know, "let's send our kids to school!" And there was a lot of criticism, you know, "who the fuck does the work?", you know, when kids go to school? Those kids would normally start working when they were five or six of whatever. And suddenly you send the to school from the age of four to the age of sixteen or fifteen, depending on the country you are looking at. But anyway, we believed in this idea that, you know, if people learn how to read and write, think and argue, and do math and all these things, that is going to be good for society. So you have a centralised curriculum: 'this is what the children in the Netherlands will learn between the age of four and sixteen'. For about a century we take care of the fact that all our citizens, in pretty much all western European countries all the citizens, at least have some basic level of, you know, their personal development. They can read and write, do some arithmetic. And then, it gets interesting at the end in the twentieth century, in the nineties, when the internet, or the world wide web comes along and you, basically, connect all these people together. All these people that know how to read and write. Some people are still smarter than other people, but still. When you connect all these people together, what do you think happens?"

[st2] "Chaos?"

|

The network society

[dr] "Well, haha, yes some chaos... But they start thinking and writing and doing things together."

[st1] "Collective creativity."

[dr] "Collective creativity, but it is also collective consciousness, it's all these things together. It was literally the reaction of the pope when Luther said:"Let's give everyone their own bible". The pope said: "No, no, no, no, no, no, no! That will create chaos! Everybody will have their own interpretation." Which was exactly what happened in the protestant church, while the catholic church still has this strong top-down model. So you could almost say, Luther was the first, you know, do-it-yourself media preacher. And so, so all these institutions that have this very strong top-down model that work within this framework of, you know, we have some elite consisting of experts and everything that then trickles down to the normal people or amateurs or whatever you want to call them, amateurs or citizens or patients, you know, you see the same thing in the care industry. And this is like the big pattern: the whole do-it-yourself thing. I literally talked to a woman, you know, who is the director of a hospital, a couple of years ago, and she said to me: "People used to come to the hospital with some kind of problem ... 'oh my back hurts', or whatever, and we tried to find a solution. These days they come to the hospital with a solution... 'Hi, I think I have this, and I want that therapy because it is better than that one' ... and no doctor has even looked at them." And she says "how the hell do we deal with this?" And I talked to a guy, you know, the director of a bank. Actually, the director of the HRM department of a bank. And he literally said: "Listen, I've been doing this for thirty years now, hiring people for my bank. I do interviews pretty much every day." And he's like, "What the fuck, the last couple of years you suddenly have this phenomenon where we have half an hour scheduled to talk to an applicant. They come in, we shake hands, they sit down, we start talking. And after five minutes these guys say, or these girls say, 'You know what? I don't think this is gonna work. I wish you a lot of success with finding a good applicant for your position' ... This has never happened before. I thought we were in charge." ... But no. No longer. I've talked to police officers, in neighbourhoods in The Hague where my university is. And we literally say, 'Oh, look at that flat. I put everybody who lives in that flat building in a WhatsApp group. And they are now looking at the street." And I ask, you know, "How do you deal with that?" I for one, I do not have WhatsApp on my phone. For good reasons, you know. WhatsApp is owned by Facebook and also the national police force says, you know, no apps by companies like that on our official phones. Which makes complete sense. I hate the company. I like WhatsApp as a product but I hate Facebook as a company. He said, "yes, but you know, they do have my mobile phone number." And I asked "But how do you deal with that? Ho do you make sure they don't go crazy over things that are not important or anything?" And he said, "Oh, you know, I organised two workshops, two evenings here in the, you know, civic centre that they have. where I basically explained to them what they need to look out for, you know, on the street." It's a basic idea, and you know, it really works. But in all these stories you hear the same thing coming back: the professional becoming more of a teacher. And so the nurses are now trained to teach the patients how to deal with their illnesses. You know, this whole idea of, you know, what you know about your illness, what you know about the therapy is an important part of healing. And so, on the one hand you do get chaos, and on the other hand you do get massive creativity. And of course the point is, you know, the art sector is not untouched by this, you know. The art sector also has to leave behind this idea of you know, we have an unlimited sort of, you know, growth of artists and professionals who know best, and that we have this other world, and that's like a plot when you apply this, and that's then design, and so design for a long time used to be called applied arts. So art is where the real thinking happens and then the designers, you know, they apply it to real life, so that's that actually aren't as interesting as art. Or at least, that was the idea...

At the same time ... ehh ... I have a bit of a presentation that ehh ... It is called 'The end of music as we know it'. So, more and more I started to realise that what we call music is not just, you know, this thing you can listen to, but it's also very much a very specific construct in our society. Venues, reviewers, and, and the commercial products like Spotify, or iPods, or, you know, the music publishers. And the same thing goes for visual arts, all the arts have their own temples. The white boxes of the visual arts, and the black boxes... We literally created environments for, you know, visual arts and performing arts, that eliminate any idea of context. Why are the walls white in museums? Because it's only the work. There is to be nothing else. Why is a performance venue black? Because it's only the performance, there is nothing else. And this is a bit of a strange idea when you look at it from a network perspective where everything is connected. So, you know, I'm basically still trying to figure out what this means, for a place like STEIM."

[st4] "What do you exactly mean by 'network perspective'?"

[dr] "When everybody is becoming creative... everybody is now a photographer, you know, we all have a camera in our pockets, and we use it. I don't mean... we're not creating, probably, what we call art —or what used to be called art... in the 20th century— ..."?

[st4] "There are exhibitions in selfies and...?"

[dr] "Actually the selfie is an interesting ... if you take a , very sort of basic ... [draws on the flipboard] there are these hierarchies, you know, and there is a bunch of smart people on the top and they tell everybody down there what life is all about. But when you have networks, you have basically, you know, there's all kinds of... crazy connections between people that you cannot control. Your employees will be talking to employees from other companies, because they are friends or they are on football teams together, or they met each other on a holiday."

[st1] "But also the resources for creativity and the resources for work and for industry become more accessible. Before it was only an elite who could access."

[dr] "The technology is basically free. You can't buy a phone without, I don't know if you can buy a phone without a camera. Maybe you can in some nostalgic way, but, you know, there will be a camera in your phone."

[st4] "And so these days everyone is an artist?"

[dr] "I don't think artist is the word, I don't think artist is an interesting word anymore. In a deep, in a deep way. I think, you know, when you take the twentieth century criteria of art, really well thought out, "expressions of an individual's perspective on society" ... no, no one's gonna be an artist... or, you know, that may stay the same. And a small elite group of people will be interested in that, in white and black cubes, that's still the same, but on the other hand, you know, and especially in music, everything has become so distributed."

[st4] "And take for example being a manager now, is there still a point of being a music manager?"

[dr] "Well, it depends, you know. The most important port of my story for you, and also for the story I am trying to develop in my head, is to stop thinking about music as a thing or a product that needs to be sold and marketed and everything, but think about musicality as a quality that everything can have. Do you understand what I am trying to say? Music is a thing, and musicality is, you know, a quality of something, a quality that you can find in anything. That you can find in care, or in the work of a police officer."

[st1] "Make things sound like music."

The best sounding restaurant in the world

[dr] "Yeah. One project that we are trying to develop at the moment is make the best sounding restaurant in the world. Basically get together, you know, chefs and color designers and architects, get all these disciplines together, not just the musicians. But to create a social space. A social space, so you also have to think about what it means to be together. And what it means to be together in a noisy environment, or maybe in a really quiet environment. Or maybe we can have, you know, all the cups and saucers tuned in the key of C. Or A minor. You know, you can choose whether you want to eat in A minor or in C."

[fb] "That goes back to Brian Eno and their music."

[dr] "In a way it goes back very far. But you know, this whole idea of isolating deep knowledge in some elite sector of society was maybe a temporary thing we did in the twentieth century, where everything came from above. Knowledge came from above. Look at what happened to knowledge. You know, we organised knowledge in schools, in university, in polytechnics, and nowadays, you know, whenever you want to know something, where do you go?"

[st1] "Google."

[dr] "Google and YouTube. You know. People learn more from Youtube then they do from formal teachers. One of my, I work for a big educational institution. But so, you know, I sometime say: 'There is more learning happening than ever before!' The question is whether the educational sector still plays a vital role in it."

[cc] "So you are talking about the breaking out of the power system of our society. What you are saying is that the definitions are limiting, because it means that certain people have the power to be those artists, and certain people don't. Those definitions were built by people who were considered, you know, learned or educated, so that certain people have the power to be those things. And so now, if we're decentralising this power, and if you can define yourself as a curator or as an artist or as a musician, a cook-musician... My question is, is it becoming more of a social act, is it an aesthetic act... with this change of definition, what is the object? What is the objective?"

[dr] "There is an object. And there's an objective. I would say the objective becomes how to make the world, in general, more... poetic... more musical."

[cc] "So it is aesthetic?"

[dr] "You know, ultimately, in our sector, the cultural sector... what our sector has to offer is some idea of aesthetics, you know. If you want to go for social relationships, you have a social sector for that, we have a care sector, we have, you know, organisations that do well-being, which are not very good at aesthetics. No one is, except us. You know, the culture sector has, you know, for millennia been the place where the only object of experiment is meaning. It's the only thing we do."

[cc] "Right."

[dr] "Whether it is ungraspable and intuitive or very symbolic and direct, it's always, you know, dealing with meaning. Whether you try to make a person cry because of a melody, or because of an artistic statement. So, what I'm trying to sort of figure out is how we could, with all our knowledge from, you know, historically from our sector about musicality, rather than this thing called music which is either, you know, a thing you listen to on headphones or a concert you go to that lasts somewhere between twenty minutes and three hours."

[st4] "It's a product now."

[dr] "It's a product, you know. And then you get into this whole thing, 'Oh! You have to market it to be...' Sometimes people say to STEIM: 'You have to reach a larger audience.' Meaning, you know: 'You have to sell your product.' Which is not, which was never meant to be for a large audience. And you have now start to sell your product, using better marketing to reach a larger audience. And I say 'no', I don't, I really don't want to do this. I'd rather engage with a care institution to make their spaces where people... this is the project we're doing, we're working with an Alzheimer care institution..."

[cc] "But that is reaching out to audiences."

[dr] "But it is a completely different model than when I have music that I want to find an audience for."

[cc] "But you're still reaching out."

[dr] "But that's, see, but this is where I think in networks everything has to start from the connections. You know, in hierarchies everything starts from the content, and then you basically, you know, you sell it, you know, and you have to do marketing. In the network society marketing, even marketing is a bit of a silly concept. If you collaborate with people you don't need to market it to them anymore. Another interesting example, I was talking to this consultant for the city of Amsterdam, and he was looking at cultural institutions like STEIM, so you go to the Concertgebouw and to the Appel, and all these institutions, pretty much all of them, they have educational programs. They have you know, educational content, like little books of, you know, interesting stories about their objects or whatever it is that they do, that they then try to sell to schools. And there's also an institution called Mocca, they are like a broker between these cultural institutions and all kinds of, you know, schools. Primary schools, secondary schools, we are talking about young kids. At STEIM we work a lot with more like higher education, with art degrees, with conservatories, and I said to this guy, 'Well, that's not how we work', you know. We work with, I think at the moment six, educations for higher education, but we don't have like, you know, we don't have a specific you know product that we try to sell to them. We basically start talking to them. Like we run a master's degree here for the conservatory in The Hague. They literally asked us: 'can you do a master's degree for students who want to design new instruments?', like what we talked about at the beginning. And we said, 'Yeah, OK, let's do that. And basically we'll treat your students exactly the way we treat every artist who comes here. Is that OK?' ... 'Oh yes, we'd love that!' ... Then there's a course here in Amsterdam that's called, you know, Master's Degree in Live Electronics. They come here with their students, every month, three days, and we do workshops with them. We work with the Utrecht school of the arts, we give lectures in their school. So it's different every time and it always depends on, you know, the relationship between them and us. We are doing the master's degree for The Hague for eight years now."

|

[st2] "I think it's very interesting because you said that you get other institutions like that are interested in what you can coach and teach to other programs. And you also mentioned that you maybe reach out to hospitals and Alzheimer, so I understand that you get some ideas, that they come ... which one are the ideas that you're reaching out, in the way of thinking of how it can go further? I guess hospitals are something that came from you, reaching out to them for working. Are there other ideas, audiences, where you want to explore the musicality with different types?"

[dr] "What we are doing now is the care sector. We've made instruments for people with disabilities, and the social sector. We work solidly together with the Beach, which is a lab, you know, even further outside the city. They are all about social design. They basically say: 'We'll go to this particular neighbourhood' (it's near Amsterdam-Osdorp, near the Meervaart), 'we're just gonna move here, we have no idea what our medium is' —interesting— (they said, we literally don't wanna choose a medium beforehand; like, we have sound and music; or if you go to the Waag, they have, you know, biotechnology; or Mediamatic, they are really into biotechnology; and the Appel is visual arts) ... the Beach said: 'there is no medium, we start from relationships; from just basically, start by walking around, getting to know people. And we have an artistic mentality, an artistic frame of mind, you know, an aestihetics oriented way of thinking about the world.' Now I literally, I did a workshop a while ago with teachers, in The Hague, with teachers in our course that trains teachers, for kids. The pedagogical academy it is called. And I said to them: 'I know that you know everything about learning. That's your field, you know. You're learning here, what you're learning is how you should teach kids how they should learn. That's fine. But is there such a thing as beauty in learning? Or beauty in education?' And they were like a little sssssssssurprised and stupefied for about one minute. And then ... pfrffff...! It exploded. And they said 'Oh, you know, yeah! There's nothing, there's nothing more beautiful than, than, than a kid who's a little bit puzzled, and then you explain something to them, and you see then moment that they get it. And, and the way they talk about it is really the way you talk about a deeply aesthetic experience. 'I loose all sense of time and space!' That's what happens when beauty really strikes you hard. You loose, literally you loose the sense of time and space, which is also, by the way, the same thing that religious people talk about when they have a divine experience. 'I had a mystical contact with God. I lost all sense of time and space'. So I think, you know, in that sense, yes, it is the aesthetic perspective that separates us from all these other sectors."

[cc] "I can have a very sociological approach to aesthetics. Because it is rooted in experience and it's rooted in exchange..."

[dr] "Yes, it's phenomenological at the same time as it is social. You know, we always want to go back to the experience: 'I'm not so interested in what your original idea is, but how is it experienced?' But it's almost like, and that's a little, to a degree, my point: this transition from a hierarchical industrial society to a messy, complex, chaotic, you know, network society, almost forces you to become way more social and sociological in you approach to whatever it is that you are doing. Whatever it is that is made is now made by everybody, you know. Artists are becoming our teachers. Not in formal situations as students, but, you know, we literally... I'm literally on a team right now, as a sound person, because STEIM is all about sound, with a woman who is into color and light, that's her medium, with a guy who is a gardener, his medium is, you know, green stuff, fake or real, doesn't matter to him —if people get happy from fake plants, why not?— and a woman who is an architect. So it's like space, nature, light and sound. And eh, it's very interesting because the, the fund that give STEIM most of its money put this team together and said 'We want you to go to this care home in Eindhoven, which is a city in the south of the Netherlands', because they have a care concept that's all about sensory stimulation. I don't know what you know about Alzheimer, but Alzheimer is a progressive disease, you know, you have initial stages and then... In the initial stages it is very important that you stimulate people. You have to keep them active, you know, the longer they stay active the slower the disease develops. When somebody's in the final stages, they really can't deal with anything anymore. They've completely lost every sense of reality, they don't recognise their children anymore, you know, everything... you have no idea what their consciousness looks like. I was originally trained as a psychologist and this is ... we have no idea how baby's see the world and we have no idea how people with, you know, in the last stages of Alzheimer, how they see the world. It's just... it's inaccessible to us, we can't ask them. So, you know, when you have, you know, people in the first stages, you want to create an environment that has, is very rich in stimulations. Color and light and sound and everything and bla-bla-bla, while in the last... And they, what they do, these people in care institution, is, is, they, they, they organise people in groups that are all in the same kind of, you know, phase of development of the disease. And so you have literally spaces that are, you know, noisy and where all kinds of things happen, and there are spaces ... So we went there and we noticed, they're absolutely clueless about all of our media. Every space sounds terrible, to my ears, every piece of furniture has been optimised for cleaning, rather than atmosphere. I mean, all the floors are hard. It's really ugly. Ehhm, there are no plants. Why not? Because, 'Ya, they eat them'. And then our gardener says: 'Why don't you put plants that they can eat?' They don't eat them on every day all day, you know! They've experimented with plants, and you know, some plants had been eaten. Just put up a plant, you know, that is not poisonous. So you got into this whole discussion, you know, what is more important? You know, things like health and safety, or quality of life?"

[st3] "When you talk about this topic in general, I do agree the way that you approach. But eh, the whole government system, the authorities that did send these people to the institutions, ehmm, see those kind of group of people as of no use anymore. You can not have something from them anymore. They're not productive. THey're nothing. I don't think they are nothing, but eh, as a society. So you give them plants, or organising their rooms, everything is extra. So I think they just want to create an environment, you know, to just make them..."

[dr] "My point is: that is exactly what happens when you take a radically medical approach. If you say it's all about trying to cure a disease that's incurable, then, eh, you know, health is important, and safety is important. So what basically happens is, you know, you lock these people up. You know, we don't want them on the street, because, for Gods's sake, you know. And another, and this is again, you know, I would say, when you start thinking about this more in terms of networks, you know, what, what other relationships could we design between these people and ... stores, you know, or in the neighbourhood, or maybe, you know, there are now experiments where we have young kids visiting old people's homes, because they both love each other, you know. And that's when you start reconnecting them back into a real world."

[st4] "So you go into this care center to make it more aesthetic. How do you go about this? What is the actual... How do you conceptualise, or what is the goal? How do you work on this?"

[dr] "We basically, you know, we walked around and looked around and talked to people and we said, okay, you know, well, I would like to re-design the whole building ... I want to, you know, put soft materials on every floor and wall and ceiling and everything ... but that's never going to happen. The building was three years old! So that's why we said, you know, it's way more interesting if we can teach the staff and the family of these people and maybe even for the people who are not yet very advanced in the disease, if we can get them to be more aware of, you know, simple sonic interventions or, you know, what plants are edible or not, all these little things that can make a big difference. If we can teach them how to work with these media, that's a more interesting intervention from us than that we take a hallway and basically re-design the hallway and then say 'ha, we designed a new hallway for you'. So it, but you know, it... and this wasn't just me who proposed this idea, but we all agreed that it's way more interesting if we make them more sound-aware, colour-aware, or, you know, light-aware, and, you know, it's about the people who work there on a daily basis. Not about the management, you know, if we can empower, the the nurses and all the people who coach them have a little bit of better understanding of how to create a space that is sonically a bit more... to use soft tablecloths, you know, instead of everything plastic and hard, you know. And you let them experience the difference between, you know, a space where every surface is hard and is reverberant, or where things are all a bit softer, you know. Or maybe we should make all the walls super white, but have a lighting that people can play with, and then the visual designer could teach the staff, you know, the effect of different kinds of colour of light. I'm giving you this example because it's an example of artists and designers now becoming teachers. You know, trying to empower a larger group of people who can then do it themselves. And so, and I think this is a very important thing if you're if you're in a course of arts and cultural management... I look. at STEIM as being, and many other places, as being infrastructure where people do their thing rather than as a place where we produce content that we give to them. Look at the media industry, the media industry itself is a good example. Who was making all the money in the media industry forty years ago?"

[st5] "TV?"

[st6] "Newspapers."

[dr] "Newspapers, publishers, record companies, you know, film companies... People who owned content. And sold it."

[st5] "Copyright holders."

[dr] "Copyright holders. Who have the copy right to the content and then you can sell it."

[st5] "That's the main business model."

[st5] "That's the main business model. However, all these companies are doing really bad at the moment. Who is now making the most money in the media industry? Facebook, networks..."

[st6] "All the networks."

[dr] "And what do they do? They do nothing! They are an infrastructure for us. So the big thinking leap you have to make is to not thinking of yourself as producing something but to be an infrastructure for something else. And hilariously —and you really have to check this out, in your culture— go to DIY stores, like the old ones, you know, where you buy wood and nails and hammers and that stuff. It's really fascinating, you will see that every DIY store now has sections on its web site about ... inspiration ..."

[st6] "Yeah!"

[dr] "They want to inspire you, they want to teach you about colour ...'What colour is best for your life style?' ... 'We have stylists advising you'... It's fascinating to see. And of course, you've got to buy wood and their nails and their hammers and their tools, but they know that if, if your thing is DIY, Do-It-Yourself, you have to help people figure out what it is that they want, what it is that they want to do in the first place, and then you teach them how to do it, and then you sell them the stuff, you know, that they can do it with. But you understand, that is a completely different model. Where everything starts from the larger context. Where meaning originates. And then you ask 'where can I contribute? And where is my expertise relevant?' ... And the old-model media companies are all going bankrupt. They disparately trying to protect their copyright. But is a losing battle. Sure, we had a new legislation a couple of weeks ago at the EU about this, but ..."

[st1] "I have a question, on this point of the hierarchical and the network society. So you believe that the network society will progress much faster? So you think that the civilisation may progress much faster? In the network?"

[dr] "I am not sure if it is faster, I think it may actually be slower."

[st2] "It is more static, no?"

Refined forms of romanticism

[dr] "Because each time it will involve more people. Basically the irritation that all of us feel, who are in the elite, you are all in the elite, we are all part of this little elite, the irritation we feel towards populists at this moment, is their dragging us back. But I think the populists, like Donald Trump or, you know, Boris Johnson in Britain, Boris Johnson in Brexit literally said: 'People are tired of so-called experts'. You know... all these populists are hard-core romantic thinkers. They do everything on intuition. They say: 'Fuck rationalism!' You know... 'Fuck thinking!'... And, you know, the rationalists in Brussels say, you know, 'we don't care about emotions'... you know, 'we thought about everything and this is the right way to go.' I think, if we do it right, and I think our sector has a very particular role in this to play. Because the culture sector is the only sector that is capable of what I would call, like, a refined form of romanticism, you know. Rather than the brutal romanticism of people like Trump and Orbán, all the populists... 'Let's go back to the fifties!' ... You know, and that's always a fifties that never was. If, if we do not succeed in involving everybody in this stuff, and, and you know... in a sense, a lot of these developments have already happened. People already have all these phones. They are already talking to each other. If we don't find a way connecting to all of these millions of conversations, well then people are going to say 'fuck you!' to the culture sector. Like they, we have a cultural research agency here in Holland —the Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau— they literally asked 'what do you think of culture and how much should we, as a society, invest in culture?' And it turns out that people want to cut five time as much money from the culture sector than we are giving it! So we are giving it one billion and we cut five billion. They have no idea. Because they see the whole sector is a bunch of fucking elitists."

[cc] "The problem is, people from a certain generation ([adressing the students] so, more my generation than your generation) they still want to be the elite. Instead of wanting to say what, how do people want to consume a museum, or how do people want the museum to be. They want to hold the power. There's still these people in power. So I think the younger generation, thís generation, will make a change. But for the people who are over fifty, I think they are the problem, in a way. Because they have the positions, they want to keep it how it was, they want to keep the French culture a certain way, they want, and not only French, but all the cultures, all the people who are holding the positions, they still have this discourse."

[dr] "And it's a wrong discourse, it'a a discourse from the twentieth century. We have to say goodbye to that discourse. Every month I do a guest lecture, a half-a-day guest lecture, for young civil servants. And these are kids from between 20 and 28 that just started working with some city or whatever. They completely get it. And they're completely depressed about, you know, all these old idiots that hang on to, you know, old fashioned, you know, hierarchical models and expertise and knowledge and money and, you know... But I think, you know, maybe this isn't the most important thing. If I look at the care sector and the educational sector, all these different sectors in society, they are all begging and searching for meaning. They know that their systems have become too rationalised. You know, and you have... so there's a couple of very dangerous values. Like, on the left you have the value of equality. Equality kills quality. You know, if we treat everything the same way there is no way you can produce quality. On the right you have things like health and safety. They kill everything too. The obsession with things that are healthy and safe, you know, basically puts us all in chains, like I said with the old peoples' homes, you can lock people up in their rooms so that they can't get into accidents in the outside world. But, you know, it's really hard to argue against equality; it's really hard to argue agains safety, you know. So, on both sides you have these... I call them 'dangerous values'. Because they basically kill every sense of quality and meaning. And it's hard to say, you know, we want less of it."

...

"There is a lot of interest in the aesthetic quality of life. Why is food becoming so popular? It's a really accessible form of beauty. We have to eat a couple of times every day. Why not make it as beautiful as possible? People want beauty in their lives. So I'd say, maybe let's begin here. Maybe design should be the primary discipline where we connect to the world. And we do crazy, you know, experiments. Designers need to, you know, need their own fundamental questions. These are the same things we now do in art. But it also means we don't have to sell art to a larger public then. If art is basically the fundamental research of the design sector, then everybody can be fine with that. None of you, including me, has any idea of what they do at CERN, you know, the particle physics place in Geneva, but somehow... and it's really a shitload of money goes there... but somehow I think I understand that we as a, you know, as people we need to do stuff like that, because, you know, of knowledge and technology or something? I have no idea what they do. And CERN is not really trying to explain it to me either. I don't think they should. As long as we have, you know, a place where these real life experiments —that's why I'm so interested in making the berst sounding restaurant, you know— these kind of experiments... need really crazy fundamental, you know... food, basically, for the designers. You have to be able to go crazy. I once visited a course in Los Angeles, it was the Pasadena Art College of Design, and they're very closely related to the automotive industry in the United States, Chrysler and Chevrolet and these companies... terrible design! Everything they did was terrible. From day one, you were designing cars. No crazy experiments, no, you know, 'let's rethink this', or 'let's rethink that'. 'How can we reframe the care sector?' ... 'What does it mean to become old?' You know, I literally... we went with a group of students in Hong Kong, a group about as international as you guys, we went to a care home, and they literally asked the guy who was running it: 'What's more important: health or quality of life?' And the guy said: 'Health!' And all the students went like ... 'I don't think so! When I'm old I'd rather have two amazing years than four years of bad food being locked up in a room with nobody to talk to. I wanna get drunk, you know, the last two years! And die of a heart attack because I ate too much good food and drank too much good wine!' ... And I guess that most of us would give that answer. But we don't organise it like that. And that's the difference we need to start bringing!"

...

|

Group picture shot by Cynthia Cervantes at the end of Dick Rijken's lecture at the IESA, Cité de Grisset, on Wednesday September 25th |

notes __ ::

(*) Michel Waisvisz became STEIM's artistic director in 1981. His involvement with STEIM, however, goes back to STEIM's founding days. [

^ ]

tags: pamp19, STEIM, Amsterdam

# .491.