Part of this year's Sonic Protest Festival were a series of lectures, workshops and performances by the American composer Nicolas Collins, a student of Alvin Lucier's, circuit bender, bricoleur, early adopter of personal computers in live performances, in the 1990's visiting artistic director of STEIM in Amsterdam, a DAAD composer in residence in Berlin, and currently editor-in-chief of the Leonardo Music Journal, and a professor in the Department of Sound at the School of the Art

Institute of Chicago.

A big part of Nicolas's contributions to the festival in Paris took place at La Générale Nord-Est, and it is there that Emmanuel Rébus and myself had the pleasure to meet and converse with Nicolas, twice over lunch, and - in between the two - a third time, in the afternoon of Saturday April 2nd 2016, set up as an informal, but audio- and video recorded interview. At the time Emmanuel & I were preparing our contribution to an international interdisciplinary colloquium on the notion of emergence in music, and it was a little bit into this and related notions, that we tried to probe Nicolas's ideas, opinions and thoughts.

But as such things go, in the end, it all spread out and became so much wider ...

Thank you, Nicolas!

Nicolas Collins - 2 April 2016, La Générale

august 4, 2016.

Below is a pretty much complete transcription of the audio recording of (mainly) Emmanuel Rébus and (a little bit) myself interviewing Nicolas Collins, after lunch on Saturday April 2nd 2016, at La Générale Nord-Est in Paris, during the set-up for the Sonic Protest Festival.

NC = Nicolas Collins ; ER = Emmanuel Rébus ; HS = Harold Schellinx

Prelude - On long string & transgender instruments

[ER] - Later this afternoon (Saturday April 2nd 2016) Ellen Fullman will give a conference on her long string instrument.

[NC] - ... that's what she does! ...

[ER] - It has a name similar to Alvin Lucier's piece ('Music on a long thin wire'), but the concept is completely different.

[HS] - She has been doing this for quite a while, no?

[NC] - Oh, it's been going on since the early eighties. It turns out ... I didn't know this actually until I first met Ellen, but... in a string the dominant mode of vibration is, you know, when it goes like this [moves his hands up and down], the Pythagorean thing, the transversal wave. But there is a way of inducing what is called a longitudinal wave, where you get the vibration going like this [moves his hands back and forth]... and it's a completely different acoustic model that exists at that point. The harmonic series doesn't work the same way. And the way you get a string to do this, is that instead of plucking it, you rub your finger along it. And you get different overtones, so to speak, I believe based on the velocity of your movement. So she made this instrument that has multiple strings. I don't know how the tuning is done, I don't know how dependent it is on tension of the string and how much is simply a function of the density, what material it is and how fat it is.

Oh, but she will obviously explain all this in an intelligent fashion.

But the most important thing about it, is this other acoustic model, which is unlike any ordinary musical instrument. I don't think that historically, in the West at least, there is a musical instrument that uses this principle. Which is kind of weird, if you figure that we've investigated seemingly everything you can do with a column of air, a bit of vegetable matter, your lips, you know, a string ... I mean, you even have the tromba marina, which is a beautiful instrument. And I read at some point that the reason it was introduced into religious music is that there was a prohibition against women playing a brass instrument. And in order to get a natural trumpet, which is to say all the overtones, to get that sound, without playing a trumpet, the easiest thing is to get overtones on a string. So it was the women's trumpet in the nunneries. It should be a feminist symbol. There actually is a tromba marina ensemble somewhere, I think it might be associated with the early music program at Basel.

[HS] - We know a tromba marina player, Abril Padilla. She also participated in one of our unPublics, though she didn't play the tromba marine then.

[ER] - And she is living in Basel, actually.

[NC] - Ha ha, you see how the brain works...?!

[HS] - But of course it actually is anti-feminist. Women should play the trumpet. We should play this tromba marina.

[NC] - Yes, we should have transgender instruments… You could do a real guerrilla piece and replace the entire Vienna Philharmonic with female players.

[HS] - Including the director!

Introduction & formalities

[ER] - So your official name is Nic?

[NC] - Legally I am a Nicolas. My mother is from Chile. So I have a Hispanic spelling. But most people call me Nic.

[ER] - Let me begin with a few trivial standard questions. Nic, you are here for the Sonic Protest Festival. Can you describe in a few lines what kind of experiments you will propose here for the audience of the exhibition?

[NC] - Let's see... I think you'll get all courses of Nic. You're getting the soup, you're getting the salad, you are getting the main plate. I am doing workshops, here in Paris and in Lille, that are workshops in hardware hacking, which is basically constructing electronic instruments that are performable instruments, using very simple electronic technology, getting at the tactile aspect of electronic music in a world of trackpads and keyboards.

I'm presenting a small installation project here in Paris, Tudor's Walk which is based on David Tudor's 'Rainforest'. This piece involves taking a transducer, which is basically a loudspeaker without a cone of paper, just the mechanical engine of it, and attaching it to objects, to turn ordinary objects or unusual objects into loudspeakers that are not transparent, they're not windows for sounds, but they have a sculptural, physical essence that changes the sound. So it's about transforming sound through physical objects rather than through electronic processing. And I have done a sort of homage or variation on it, where there are these small transducers that people pick up from a desk, and they plug them into their phone or their iPod, and they can play back any music through these and then touch them in objects all around the city. You walk out of the space, you go around town, you find a garbage can, you find a car, you find a door, you find a dog, and you press this against it and you see how it changes the sound. And then you also have a stethoscope, so when you place the transducer on the car door and you vibrate the car door, krrrrrrr, you put the stethoscope on the car door to listen to it more closely, and then, sort of like a contact microphone but without electricity, you can hear all the detail.

So that's the installation. You have workshop, you have installation ... and then I am doing some concerts in the various venues that are associated with the festival. And the concerts are a mix of work. Here at La Générale, for example, I am doing one piece that is almost the oldest piece I have ever written - back when I was a student I did it, and I revived it in the last 10, 15 years, it uses feedback to create a sort of a raga-like setting, based on the acoustics of the room; and then there is space within that piece while the feedback is going on for a musician to perform both sound, which interacts with the sound of the feedback, and movement. The movement can be used by walking through the space. You can change actually which pictures are coming out of the feedback, it's a very hypersensitive system that uses... Actually I think it's one of the only pieces of music I know of that uses both positive and negative feedback in the same work. And then more recent pieces that are much more easier. I would have to say they are probably much more irritating. And they are based on... after years of being very immersed in minimal practice, in the last few years I got much more interested in chaotic systems. Most minimal systems are sort of the opposite of chaos. They are about reducing chaos down to its fewest elements, whereas now I am much more interested in using unstable systems to generate new forms.

On education, soldering and a misspent youth

[ER] - You are using a lot of technical terms and scientific words, like 'feedback', 'chaos'… do you have an education in science? Or an education in music? Or both?

[NC] - (laughing) I have a misspent youth. Let's see. I do have an education in music. That's sort of what I majored in when I was at university and got subsequent degrees in, though many many many people have accused me of not making music. So, the question is whether I was properly educated. Or not. In other words, if you enroll in a mathematics course, in analysis, and you fail the course, can you be said to have had an education in analysis? That's a philosophical question...

[HS] - So you maybe failed your music courses?

[NC] - (laughing) Yeah, so I think I maybe failed music. Though they passed me! I think it was a failure of the culture, perhaps… No, in all seriousness: I studied with very radical composers. I studied for many years with Alvin Lucier. I had close associations with David Tudor. I have done work with John Cage. I was very close to the emerging generation of composers of my age that studied under Robert Ashley and David Behrman at Mills College… So I was, from early age, educated in a very avant-garde setting as opposed to, say, that generation: the Lucier generation, the Cage generation, the Phil Glass generation. They studied at a conservatory, they can really be said to have been musically trained. Before they went through that catharsis and then changed. So yes, I have a music education, but I should temper that by saying that it was in a time of great avant-gardism.

I am not … well-trained scientifically. I come from a line of mathematicians. But I had anxiety about math as a result, and no particular talent. I re-entered mathematics when my son was quite young, because he was very very, very smart mathematically, and interested in the intellectual aspects of it. I was never trained in electronic engineering in any way. I only have a sort of rudimentary grounding in general physics, though I did very intense study of acoustics, as, I think, most composers do.

Probably one of the major differences in education between the United States and Europe has to do with the ability of young people to enter a college having no idea what it is they want to study and leave it with a degree in some subject after four years and still not have any idea what it is that they wanna study. I think that good universities in the United States are one of the last remnants of the renaissance education, where you can take a distribution of courses between the sciences and the humanities and craft a diet that suits your own intellectual curiosity. A friend of ours once said that the average European leaving university knows more, but the average American leaving university knows more about how to know more.

[ER] - I was lucky enough to meet Alvin Lucier at his university the last year he was teaching there, and I asked him about the scientific aspects of his work, and whether he was interested in, for example, understanding the physics of 'A Long Thin Wire'. And he told me, no, he is not interested. He probably knows some physics, but he doesn't want to present this element as being of a big importance for him. Is that different for you? Because you are also known for writing books, for example, in which you explain people how to solder circuits, so you…

[NC] - Well, soldering is not science...

|

| Nicolas Collins's ENSAPC workshop presentation @La Générale, on Sunday April 10th 2016. |

[ER] - But there is in that book - 'Handmade electronic music' - something like a progression in difficulty, it's organized, and there some concepts that are introduced… So my question is whether this is only a technique for some goal or whether the construction work... I feel actually that the device that you make is part of the art work in some sense.

[NC] - It's a complicated question. I think there is a sort of a continuum of understanding one's technology, that affects how you work with it. For example, I think that a good violinist has a very good understanding of the instrument from the standpoint of a player, but may not be able to build an instrument as well as, say, Stradivarius could. I don't know whether Stradivarius was a good violinist and I don't know that he was a great composer, because we have no remaining documentation of that. So there tends to be a question of domains that overlap, but are semi-exclusive. Right?

I remember when I was a student that there was a tremendous chauvinism in the air in America about trying to prove that there was such a thing as an American music that did not sit on the shoulders of Bach and Beethoven. And in the field of electronic music much was made of the fact that, when Stockhausen went into the studio to produce a work, there was an engineer who stood between him and the actual objects. Right? So, what are we? Are we a violinist who has a nurse practitioner who is actually playing the instrument while he sort of waves his hands, like this, or are we the composer who is delegating to that violinist? There are degrees of separation between the concept and the execution at play here. The Americans may have been justifying their own poverty when they said: 'Oh, we don't need engineers'. That may have been their way of saying: 'I can't afford an engineer', because we couldn't.

So you have a generation of... artists like David Tudor, David Behrman or Gordon Mumma, the first people who began to construct their own instruments out of electronics. And these are the people that I studied with. And we knew that we were not engineers. We knew we were basically... at best we were musicians. But we were curious. You might call us hobbyists, and we were interested in making these instruments. We tried very, very hard to understand what we were doing. Behrman and Mumma and Tudor tried very hard to understand what they were doing. They would read technical manuals. As far as they could. And then there would be a mathematical transform that they couldn't get, because they didn't have the math skills to do it. But they tried very hard.

And I will have to say that, within the limits of my intelligence, I did as well. However, the most interesting electronic music arose from misunderstood circuits. And there was an air of indeterminacy and chance that permeated in many, many flavors the post-Cagean music world. And having circuits that didn't work quite right was like putting a little Cagean monosodium glutamate into every piece. Tudor's ensemble was called 'Composers Inside Electronics', and everyone in the group received from the master this sort of notion that a circuit indeed contained an element of the score, whatever the identity of the music was, it lay in the silicon.

What's interesting is that I went from making circuits in the seventies to doing a lot of work based on programming end of the seventies, eighties, nineties, but I always did work with hardware at the same time, it was always a mix, it was always a balance. So when I started teaching in 99 my students asked me to put together a course in circuitry, because circuitry was back.

Anti-theory

At the end of the nineties everything was digital. I like to say that, 'Control-X, control-V', ..., you can cut the world. Right? You can use the same tool, it is like having a pen that you can cut video with, you can edit a text that you've written, you can cut HTML code for your web site, you can edit audio, you can graphic design, you can do Photoshop... one tool to do all of this, it's incredibly powerful. But at the same time, unlike a pencil you can't actually move like this with it. You've lost the tactile sense. You cannot really touch things, unless with a trackpad and a mouse. And a keyboard.

My students - art students, not music students - had that disconnect in their lives where the digital was so powerful, and so useful. So easy, in certain ways. But that sense of being messy, that is I think in the heart of every artist, was being restrained. So they said: "Can you teach a class in doing musical circuits? So we can see, that's a tactile thing." And at the time I started this thing, which then led to that book, circuit-bending had just sort of come up. That was something that came up in the nineties. Reed Ghazala used to write in 'Experimental Musical Instruments' about this. And Ghazala was very interesting, because he called what he did anti-theory. And if you look at the roots of circuit-bending, the whole idea is to take a found object, a toy, and knowing nothing about it - what chip is it, what's the value of this capacitor, what's the value of this resistor - ... you make random connections, and you see what happens.

And you know, we did this in the sixties and seventies. But it wasn't our philosophy. At a certain point we may have fallen back to that, like: "I do not know what to do, let me just try this..." But it was really with circuit-bending that that was elevated to an ideal, other than a fallback. So this is a long roundabout way of getting at your question which is: "Do you think about it in terms of a science, do you think of it in terms of engineering, you've written a book in which things go from simple to complicated..." Yeah, they go from simple to complicated, the same way learning to drive a car or learning to cook goes from simple to complicated. But when you learn to drive a car or learn how to cook you not necessarily require to read a complete history of automobiles or the history of cuisine. You're not necessarily learning about the biochemistry of cooking in terms of the sort of organic chemistry that is taking place. And I think that for me one of the great liberating things about looking back at ... maybe it's electronic engineering ... from the perspective of the circuit-bending movement, was that actually you could open certain doors by not learning things, that you might not get at if you really try to understand the theory.

Analog vs. Digital, Discrete vs. Continuous

[ER] - You mention the digital cut and paste concept, the kind of universal way of handling sound, video or anything, and you also mentioned the idea that people want to come back to something more physical or tactile. This leads me to a question that has been asked already many times, and I know that the answer is subtle, but do you think that there is an essential difference between digital sound and analog sound? In a way digital will be very clean, 0 and 1, and of course you can approximate an analog circuit with digital equipment, and you can approximate it in very good ways, so that if you do blind tests, it will be very difficult to distinguish.

But, still, many people feel - like me actually - that there is something unique to analog sound, though I cannot actually find a scientific explanation for that, because, as I said, the digital modeling can - if you do it carefully - be very good. But at the same time, me and many people come back to cassette tapes, come back to much more continuous things, 'continuous' in the mathematical sense, as opposed to 'discrete'. So the question is, do you also have this feeling that there is something intrinsically unique to analog sound and analog signal?

[NC] - I think that even the way you are talking about it... you are not acknowledging part of the fact, which is, that when you say 'the sound itself' then you immediately start talking about 'the tape, the this, the that'. So you are actually not talking about the soundwave that is coming out of the speaker. You refer to the blind test which is the soundwave coming out of the speaker, and you admit that under those circumstances indeed they may be identical. I think that in most cases it is very difficult for people to differentiate between the waveform that hits their ear and the chain of production that leads to it. And it is a question of how far back you go.

Anyone who uses a vinyl record and say an iPod will be aware of the fact that preparing to hear the sound is a different process for those two things. There is a different ritual. And it is not necessarily that the one is richer than the other, or the one is better than the other, but you can not argue that they differ. Accessing a file is very different from pulling a record from a cabinet, taking the thing out of a sleeve, pfff, blowing the dust off, putting it down, putting a needle on it and being a little too early or a little too late... These are all part of the total experience of listening to the music. Right? And I think those are critical elements.

I'm not a golden ear, I'm not one of those people that can discern these minutiae of sound. But I'm very, very conscious of all this other stuff I just described. I think these days, to be perfectly honest, the actual sonic distinction is getting smaller and smaller and smaller, with high resolution stuff. I think, you can, under most circumstances, make a higher quality sound, a sine wave, digitally, even though it's step-approximated, than you can in the analog domain. If you take like an inexpensive analog synthesizer and you look at the waveform of the sinewave, and you compare it to a screenshot of the output of your laptop making a sine wave, with Max or PD or Supercollider, you actually gonna get a cleaner, more sine-like, sinewave out of the computer. But I think those other aspects of the production of the thing are incredibly critical. Because they color our impression of what we're hearing and in a way that is as significant as the actual waveform.

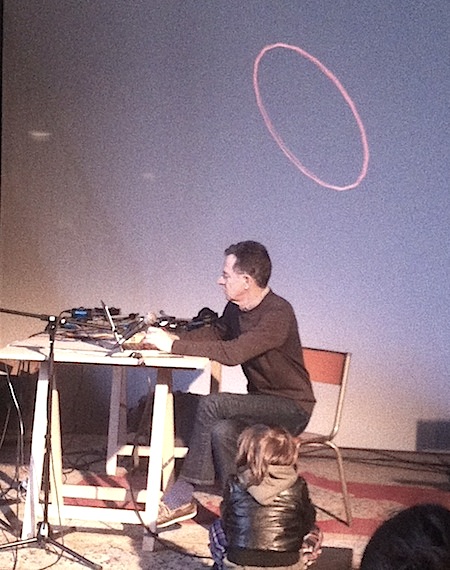

|

| Nicolas Collins performing @La Générale, on Sunday April 10th 2016. |

[ER] - But do you feel that music or sound (due to the idea of the physicality of sound, and - as you mentioned - sound is basically a wave in the air) is a continuous phenomenon? Or can it also be discrete? For example, if you have a score of a Bach piece, there are separated pitches, rhythms... Is it important for you, this notion of 'continuous', as opposed to 'discrete'? When you throw a stone on a lake, you see the waves continuously moving. But a score is discrete, it is like a program for a computer.

[NC] - I haven't really thought of it in these terms. Musical events usually have a beginning and an end. There are some people that worked sort of at the extremes of those. There is the Cage piece that is being done with the organ in Germany ('As Slow As Possible'), there is the La Monte Young 'Draw a straight line and follow it'. At the other end you have hardcore music and various other experiments have been done working with extremely short duration. I will have to say that at various times in my life [...] when I have tried to look at my music and figure out what it is and what it isn't, and I have been in a position to say: 'Let's see .. I'm not interested in melody, I'm not interested in rhythm, I'm not interested in harmony, I don't write lyrics... what's left?'

[laughs]

Isn't that kind of ... music ... that I'm eliminating?

Structuring time

And there have been times that I thought, at the most fundamental level, when people come and say: 'That's not music!' or 'That is music!', that the single most critical element is the structuring of time. And that is something that obviously exists in other media, like film and theater and dance, except that I feel like that is the principal element in musical work. You can literally strip everything else away and still have a piece of music. Look at 4'33". All that is, is a structuring of time, with no intentional control of the sound material. So that would be the paradigmatic work that probably influenced my thinking on that. So I don't think about the continuity or the division as being so critical a distinction.

[ER] - But do you think that time is a continuous phenomenon, or do you think that time can be correctly described by a very quick click?

[NC] - Well ... God, this is like philosophy ...

[ER] - Some people believe that we are rather something like a computer experiment, that we are cellular automata, that everything is digital. Some people think in this way... But I am more on the continuous side.

[NC] - It's interesting, because I once talked, in the mid- or late nineties, with a programmer I worked with at STEIM in Amsterdam, when for the first time you had computers that were fast enough to do real-time sound processing on their own CPU rather than a special purpose digital sound processing addendum. And they were fast enough to do video image processing. And this guy had done both sound manipulating programs and image manipulation. And he surprised me one day by saying: "You know, it's much easier to program image manipulation than sound. You think of it as having so many more parameters, except, you should remember that video is discrete frames. And each frame is a field, and you know you will have, from a computer standpoint, you have a big wait period, a pause, in which you can work on it before the next thing comes around." He says: "In sound you don't have that!" When you're processing sound in software, you are actually working as fast as you can. There is no wait. Everything is literally real-time. Which is why for so long early computer music was not real-time. All the numerical calculations would be done, and then they would essentially be stored; and this could take minutes, hours, days. Now that's done for animation all the time, and for video editing and stuff this is very common, you work off-line. But you can't do that if you are making or treating a musical instrument, it has to respond continuously.

So clearly there is an aspect of continuous time that is wedded into music, from a standpoint of digital production.

At the same time, look at something like an electric guitar. You can hit a guitar string and basically put the instrument down, go out and have a smoke and come back. And it's still going. So you can work on an event-driven model for a lot of forms of music performance, that does tend to challenge that idea of the continuum. The instrument acts continuously, but the actor doesn't necessarily have to be engaged in the same time… Does that make any sense?

[ER] - But in that case the action of the musician would be like an accident in a continuum...

[NC] - I don't think Heifetz would enjoy having what he does called an accident, but I know what you're saying. Yes! ... So all I can say is, there are certain very real engineering elements, like my observation about the nature of programming, but then there are also ones that are in a sense more philosophical, in terms of how you divide responsibility between the different actors in this process: you have the machine, you have the human, you have the score... and each one is parsing time in a subtly different way.

Emergence

[ER] - Typically people want to explain how some big, complex systems show an emerging behavior. For example, you are made of cells, blood, a brain, and many things (that you can describe in kind of a discrete way, by the way). But many people believe that you cannot reduce your self to the collection of your cells and your neurons, and that at some higher level something happens in this very complex systems, so that something like 'consciousness' or 'thinking' can take place. In some other understanding, in a very reductionist way, people program things, like Conway's 'Game of Life' for example, a very simple program that can show a very complex behavior, and they believe that without taking into account some higher level unknown phenomena that we are not aware of, just in a purely mathematical way, you can describe what could be called 'emergence'.

Do you feel that in the smaller context of music... let us consider, say, a musician, or a composer, who will typically make a score, or organize some kind of improvisation in some context or other, do you feel that they expect something which could be called 'emergence'? For example, it seems obvious that the score is not the music. So when you write a score, do you really expect that you already accounted for everything in your mind, and that you can hear your music just from reading the score? It is actually what they told me when I was studying music. My teacher told me that I would be skilled in music when I could just read the score as a book, and without any instruments experience the music.

[NC] - That surely was a model for a long period of time. Up to the end of the 19th century, I think the idea was that the score ... no, let me put it in another way... I have to say there was a window, from say mid 18th to the end of the 19th century, where the idea that the score embodied the music was pretty well-accepted. That it was the music. But before that, if you look at Bach, there is a lot of extra musical information that is not in the score. The dominant culture was such that you did not have to say certain things. If you look at indigenous musics from most parts of the world, the score is practically irrelevant and ownership of composition is put much lower down in the scale of values. I think that there is much greater value placed on the music as a real-time event, as a social event, all these things.

But then in the 20th century we got at the one end total serialism, think of Boulez, or Ferneyhough, of hyper-specifying what you want; and then you get for example the La Monte Young piece I just mentioned, 'Draw a straight line and follow it'. Can you hear that piece when you look at the score?

And then in the sixties and seventies you get these traditions of ... two things, both the graphic score, which cuts across many different musical styles, and prose scores, that were like recipes. You can't apply harmonic analysis to the score of 'I am sitting in a room'. And once you know the piece, you can look at the score and kind of remember what it sounded like, but it's not a linear process, it's not like looking at that Bach score and hoping you can be able to hear the counterpoint in your brain. It begs the question of what's the important thing about the music. Is the important thing in the La Monte Young piece or in a Lucier piece that you hear the actual sounds, or is the important thing that you understand that inner essential structure? In which case maybe they're a great improvement on scoring. Because you understand 'I am sitting in a room' after you read the score. You understand what La Monte Young is trying to do better from reading that score than by listening to a hundred hours of his music.

...

'Emergence' is a word that I think has such specific meanings in different fields that I do not think that I want to try to link it to any of the things that I know about.

On habits and - not so free - improvisation

But I do know that when composers like Zorn created their game pieces, there was very strong desire that this score, this set of instructions, this tactics, had value in terms of the music they would generate. Not just as a pretty document, or as an intellectual pursuit. They were really meant to be a catalyst for a musical event, and I think... you look at those early pieces of Zorn and he was addressing something that improvisers around the world were trying to deal with at that time, which is: habits.

We all know that free improvisation isn't really so free. You find very quickly that musicians have developed habits. Derek Bailey did that wonderful book on improvisation, in which he introduces the term 'non-idiomatic improvisation' to describe that sort of free improvisation that was taking place at the time. When he did the second edition of the book, at the end of the nineties, he did a new introduction and he said: "You know, when I first wrote the book, I referred to this thing called 'non-idiomatic improvisation' ... ? Now it's an idiom...!"

In other words, he acknowledged that, no matter how free and experimental the music may be, the nature of people, if they are not given directions, is to fall back on their habits. So, I do not think that improvisation needs instructions, but don't deceive yourself into thinking that it can ever be free of habits. You can give a musician who only likes to play Scriabin a Cage piece or a Boulez piece. And he may hate it. But he won't play what he would play otherwise. In that sense it causes the emergence of something. Because that would not emerge without that. Right? Zorn is a good example. He used those scoring tactics as a way to get improvisers out of their habits, changing the way in which people work.

[HS] - What is your own approach as an improvisor, in improvised musics?

[NC] - I've done the game pieces, as a musician. The instruments I worked with have always been very, very crude, so I'm never pushing the degree of freedom that a typical player has. My instruments are much more constrained. When I was doing improvisation, it was mostly collaborative. The principal purpose of the instrument I played wasn't a function of making an active contribution to the sound texture, as much as it was affecting the way other people would play.

The instrument I had was sort of a strange kind of a system for live sampling and signal processing. And the way it worked: I would tend to grab a sound from a musician, make variations on it for a couple of minutes. And what it meant was that the other musician could never escape a sound they'd made. And most musicians like to play something and move on. And this was sort of years before looping pedals. But what it means was that in a sense it forced the musician to not move on as quickly. One of my colleagues said that I slowed down the speed of improvisation in New York. I just brought it down to 4 kilometers per hour where it could go at 190. So I had a very, very specific role.

On the other hand, I think that literally every single performance piece that I've made for other musicians, as well as ones for myself, involve an enormous amount of improvisation, in any way you might want to interpret that term. It is not specified on a piece of paper what you do from one minute to the next. even when I have computer generated stuff that you look at on the screen, it's never describing all of your behavior. You always have to... I always have to trust the musician to make a large number of decisions based on a small amount of information. And there are various systems I've come up with for guiding them and for trying to push the musician to do something that, if not revolutionary, is at least fresh.

End with feedback

[ER] - As a final question, would you agree that 'feedback' is a fundamental principle of music?

[NC] - I think for some types of music, yes, for most traditional forms of music there is a very tight sense of feedback. Most instrument performance is based on feedback. Getting a sound out of a flute, getting a sound out of a saxophone, getting a sound out of a violin, is about a very delicate form of mechanical feedback, which is a sort of always compensating, and that is feedback in a cybernetic sense, of negative feedback, where you are just in the system. Tuning is about that. Compensation within an ensemble, between players, to maintain tuning and tempo. However, I would also say that there are some people who very specifically try to break that loop. Feedback and causality are very closely linked. And I know that Cage for example was very opposed to the idea of cause and effect in music. And in a lot of his pieces he works very, very hard to try and avoid that sort of continuum that comes from feedback, and tries to keep things working in a much more isolated fashion, always using as a model the physical world, the natural world. He said, "animals and movements of air don't coordinate themselves the way ensembles do, you should aim for that"; that is a certain kind of Gestalt sound that is curiously devoid of feedback on a meta-level. So there are models that violate that principle.

And there is also that sense in which the word is a crude word in English, because we also use feedback to describe positive feedback, which is what happens when a microphone and a speaker feed back. A lot of electronic, basic analog electronic processes, generate sound by having feedback that exceeds 1. So that is the opposite of control feedback, that's the other kind. And that is present in very many types of instruments, both electronic and acoustic, not necessarily part of the compositional process but part of the sound making process; but again I wouldn't say it's universal, I think there are systems that do without it...

...

... I'm afraid I really loused up the answer that you wanted ... by saying ... "Nehhh ..." ...

...

[ER & HS] - [laughing] ... but that's good ... ! ...

...

|

| Nicolas Collins performing @La Générale, on Sunday April 10th 2016. |

[ You can listen to the full audio recording of our Nicolas Collins interview at Radio On Berlin, broadcasted at ir-regular intervals. Check the schedule! ]

tags: Nicolas Collins, emergence, analog, digital, time, discrete, continuous, feedback

# .469.

SoundBlog entries around and about La Générale Nord-Est:

(2024, march 9) - Orlando & Artaud wed bound at La Générale, even

(2022, september 2) - Three Musketeers Musicking Maastricht & La Générale

(2022, july 2) - X-unPub

(2021, june 13) - Die Stillgestandenen (The Stillstands / Standstills / Stillstanders)

(2021, february 21) - Lento (slowly)

(2018, september 01) - t'Obsolete or not t'Obsolete ... [part iv]

(2018, august 13) - Rage, rafts & refugees

(2018, august 10) - t'Obsolete or not t'Obsolete ... [part iii]

(2018, july 21) - t'Obsolete or not t'Obsolete... [part ii]

(2018, april 10) - La Générale Nord-Est (PAMP18-1)

(2017, august 19) - t'Obsolete or not t'Obsolete ... [part i]

(2016, august 04) - Nicolas Collins - 2 April 2016, La Générale

(2015, july 15) - Bridges, troubles, water - unPublic #19

(2014, april 08) - La physicalité du son. Tome 1.

(2013, december 13) - Candles, Cassettes & Champagne - unPublic #4

(2010, december 29) - Obsolescence

(2010, august 14) - "And what about Yi Sang?" (이상 à Paris [iv])

(2010, june 29) - Ceremonies (Yi Sang 이상 à Paris [iii])

(2010, june 25) - Read me a poem, Yi Sang! (Yi Sang 이상 à Paris [ii])

(2010, june 13) - Yi Sang 이상 à Paris [i]

(2010, january 13) - Art fleas (puces de l'art)

(2009, july 20) - General Acoustics

(2006, august 14) - placard : la générale (Belleville)