|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

november 19, 2008.

About eight years ago, in november 2000, the trio Lee Wenham, Raymond Betson and William Cockram, orchestrated a spectacular attack on the Millennium Dome. Leading a group of local London villains, they used a JCB digger to break through the perimeter fence, punched a hole in the side of the Dome itself, and next attempted to smash their way into a display case containing a collection of diamonds with an estimated worth of no less than £ 350.000.000, using sledgehammers and nail guns. The jewels that they were trying to get their hands on included a 203 carats stone, the Millennium Star, said to be one of the finest diamonds ever discovered. A spokeswoman of De Beer's at the time called it the international diamond market's equivalent of a Van Gogh or the Mona Lisa.

The London Millennium Jewels robbers' unavailing audacity kept crossing my mind when last

week I went to have a peek at For the Love of a God, that for some

reason I keep erroneously referring to as "the God of Love": a

work by YB postart star Damien

Hirst, who in pictures I continue to mistake for U2 singstar Bono.

FtLoG is a platinum cast

of a human skull covered with 8.601 diamonds. The skull is currently on

show in the Rijksmuseum

in Amsterdam, home to a great many works by Rembrandt

van Rijn and other long dead dutch

masters. The (material) value of FtLoG

is said to be some £ 15.000.000. Its (art-)market value is disputed, but

Hirst claims

having sold the work to a "consortium of businessmen" (allegedly including

himself, as well as White

Cube gallery owner Jay Jopling) for £ 50.000.000.

In cash.

Even though

it does not come close to the worth of the Millennium Jewels, this - one way

or another - still looks like it would make for a highly stealable

object, what do you think? Relatively light, easy to hide, easy to transport

and very valuable.

The Rijksmuseum is in the midst of a painful, long and expensive renovation.

Its main building has been closed for already many years now, and will surely

not open up to the public again before 2013. At this moment only a small

part of the museum's collection can be viewed. That's in the building's

south wing. With also the modern art museum being quite literally out in

the Amsterdam streets while awaiting the just so slackening finish of its

premises, the Amsterdam Museumplein is as much of a building excavation

as is most of the rest of the dutch capital. Little around the Museumplein

would raise less suspicion than the advent of a couple of cranes or diggers.

I suggest you take a crane.

Best way in and best way out will be through

the roof.

Best time? Tuesday morning, around 6h30.

(Don't try to be subtle,

just break on through to the other side.)

|

|

Myself, I went in through the south wing entrance early in the morning of november 6th, past a mobile police post with plate glass windows that probably is

part of the 'undisclosed additional security measures' that the museum took for the time it has to take

care of FtLoG.

Upon entering the museum one also has to pass by an airplane embarkment

type of security and 'luggage' check. These I'd guess are also part of the 'additional measures', and not part of the usual routine. I tried to

make a picture of the security passage and guards with my cell phone, but immediately there came a young and angry one running towards me, shouting and

shaking his finger that it was

"absolutely forbidden!" to take pictures ...

I did not insist.

I went in at a good time. For as a matter of fact there's hardly a thing

that I find more disagreeable than museum exhibitions where visitors, for

the lack of a system with rails and small Disneyland-like trains, are being

driven to shuffle in double or even triple lines from entrance to exit along

the art works. I went through such ordeal in parisian museums more than once

too often. But that morning there were hardly any visitors yet, so there

was no waiting, and there were no lines. ( * ) I followed

the signs that said "For the Love of God". These led me up the

stairs (Rotterdamse Trap), walked me through room #8 ('Rembrandt

and his pupils'), and then through #9 ('The late Rembrandt').

Not yet

thirty minutes later I saw more and more people getting in line

before being allowed near the God of Love. When I arrived there

wasn't anyone waiting, so I just went on and felt my way in. One

has to, because it is pitch-dark and one has to pass through a couple

of small straight narrow labyrinthine corridors to get into the "shrine", which,

apart from the obligatory 'exit' signs, is of a complete and unabridged

black. Only 15 visitors are allowed inside at the same time. I actually

think that's an awful lot. I was lucky to find myself in there alone.

The skull is placed in a cubic glass show case on a black pedestal standing

in the middle of a not so very big room. It is posed a little below the average

person's eye-level, so that most of us will be looking somewhat down

upon it.

It is well-lit.

Very well.

Many viewers when finally standing skull to skull with Love/God,

commented that they find him so much smaller than they had expected. That's

surely due to the mass of bigger-than-life-sized images of it that they saw

before.

For this I came prepared.

With the exception of Rudi

Fuch's somewhat over-pathetic introduction, I think the book is really

good, though. Including tons of fine drawings and pictures, The

Making of the Diamond Skull

brings you a Study of the reflection and refraction of light in diamond

taken from a 1919 book on Diamond Design, an explanation of the mineral

and carbon structure of diamond, and no less than five technical reports

on the skull of which Love/God is a precise replica: a report

on the measurement and bioarchaeological analysis of the skull, a report

on the estimated age of the skull's teeth, an explanation of the

results of radiocarbon dating, a report on a general analysis of

the skull and a report on the use of CRANID (a computer program

that compared the skull with a database of 2.870 skulls in 66 samples from

around the world) to evaluate the likely ancestry of the skull.

Here is what all this applied science has to say about it: the first report

concludes that this was the skull of a young adult male, probably exposed

to stress between the ages of 3-5 years, and possibly again at the age of

8-9 years. Radiocarbon dating dates the skull back to between 1720 and 1810.

The estimated age of the skull's teeth is 35 years. Also the general analysis

concludes at a young adult, most probably male. On the other hand, it turned

out to be impossible to say something with certainty about its ancestry.

The skull seemed to be a near perfect 'average', as, interestingly, it blends

"all the characters of the variation seen in the modern human species".

Now could

an artist ask for more?

Best of all the faits divers I found the one stating where Hirst

got the skull: he bought it in Islington, North London, from a taxidermy

shop by the name of "Get

Stuffed" ...

The thing is blinking like hell. But that is hardly surprising given the thousands of diamonds

on a such small

surface. There's even diamonds in the nose hole, and also the cavities of the eye sockets have been covered. Like most skulls,

also this one seems to be laughing out loud, an impression that here is even the stronger because of the full-minus-one set of well-cleaned

- original - teeth that line its wide open mouth. The dark, the spot lights and the diamonds make for a very mockingly laughter.

I feel like I have entered Ali

Baba's cave, but I am also well aware that all was set in order for

me to feel that way. The large pear-shaped diamond on the skull's forehead,

surrounded by a number of smaller pointed stones, is like the jewel

in a turban ("For The Modern Prince"). That in turn made me

feel like I had chanced upon the set of a pirate

movie where any moment now Johnny

Depp or maybe even Keith

Richards himself would come crashing through the ceiling. (I actually

do consider Richards as a most appropriate owner for the Love/God

(unlike George

Michael), and I really hope that eventually he will realize as much

and decide to buy it...)

I slowly walked around the cubic glass case, watching the skull's and my

own reflections in the glass from several angles. After a while my eyes

began to get used to the dark, and as I looked around, I saw the walls and

ceiling covered by a great many faint spots, reflections of the

light by the diamonds. And I wished that the skull would start to turn around, slowly, like

the cheap disco balls that were hovering over

depressingly small & empty dancefloors in the back of 1970's village bars...

It was pretty much automatic that I pointed my cell phone camera, and took a picture. It gave me the scare of a life-time when

at that very moment someone suddenly came jumping at me. I had not noticed the guard

that had been there all the time, silently standing and watching me watching the Love/God from one of the dark corners.

She yelled at me

in broken dutch, reproachingly: "Niet foto's, verboden meneer! Nergens

foto's niet! Leest U dan niet, dat staat er toch!?" ...

I shrugged my shoulders, but I did obey and put my phone away.

I did save my 'illegal' shot, though.

Here it is.

I like it. It's black and vague. I find it scary.

|

Now let me stay far from the ongoing heated

discussions on whether or not Love/God is 'art'. It is not

the first time of course that that question has been raised in relation

to some work(s) or other, and it will surely not be the last time. Interesting

and intellectually challenging as such debates may be, I do think that in the end they

are just as pointless as the ever-recurring questions about whether this or that

type of organized sound should be called 'music' or not.

As long as 'art' and 'music' remain major cultural categories, all that

is (re)presented in and through the institutions that - whether it is by

administrative force, by economic force or by both - are labeled by these

categories, will be 'art' and will be 'music'. That simply is a matter of

fact, whether one or the other agrees with that fact,

or not.

Largely this is because there can be no

objective ('value-free'), clear-cut definition, other than that, on

the production side, 'art' is what 'artists' do, just as 'music' is that

what 'musicians' do. The postmodern age broadened the category of 'art'

to a pretty much unlimited number of acts and actions, and it opened

up the category of 'music' to pretty much any sound one can imagine. Which

by the way does not mean that pretty much anything is art or music.

Only that pretty much anything can be so potentially.

As a result, maybe 'yes!' that art's become a fair.

I for one never before have found it to be so much fun ...

Several critics and historians find it difficult to accept that in the end there

are no 'uniquely cultural objects', and au fond society and culture appear as being more or less interchangeable.

They then cringe at the sight of a 'culture' that is shaped and created by 'money, the media, and popular entertainment'.

This is at the heart of, for example, Donald Kuspit's essay

The End of Art,

on the cover of which there is a picture of a glass ashtray filled with cigarette stubs, a detail of Damien Hirst's

Home Sweet Home (1996).

It's difficult not to agree with Kuspit's observations on many of the ongoing mechanisms, but I do not share his

fear. Mainly because I am convinced that his conclusion that as a result

"contemporary culture must satisfy mass taste" (emphasis is mine)

is not correct. There are evermore signs that indicate that art itself

is tiring from the enduring mix-up of pop and high culture, and that we actually seem to arrive

on the verge of exit from what Kuspit considers our 'postmodern hell',

in which commercial status and cultural status are one and the same.

(cf.: Nicolas Bourriaud's Relational Aesthetics, Altermodernism, ETC. Monkeybusiness - upcoming)

It's easy enough, as long as one may choose.

Of course For the Love of God is art.

It is also a fine work of handicraft, executed by a whole team of craftsmen from Bond Street Jewelers Bentley & Skinner. And yes that it is extraordinarily extravagant. Which I guess is its main attraction. And no, it is not ´beautiful´. At least I do not think it is.

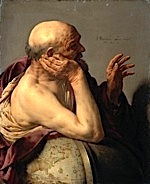

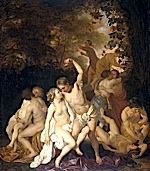

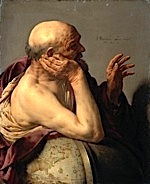

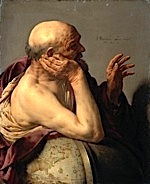

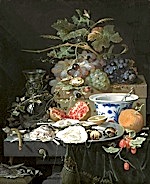

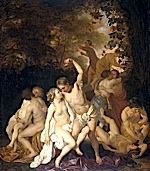

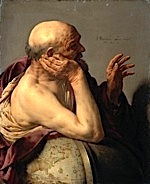

The Rijksmuseum's new director Wim Pijbes counts on Love/God attracting a new, different, cooler audience for his museal classics, that will continue to suffer from strain by continuing renovations for another five years or so. And maybe taking some inspiration from for example Jan Fabre's recent Louvre show, the museum invited Hirst to make a personal selection from the works of its collection of 17th century art. He selected 16 paintings, that are on show in the room next to the skull's shrine. You saw them all passing along the right side of your window, while you were scrolling down this entry, in the order in which they are exposed (all pictures were taken from the rijksmuseum.nl website). Apart from formal criteria and impulsive 'liking' there doesn't seem to be much of a plan to Hirst's selection. But each painting does come with a dedicated poppy comment by the YB (self acclaimed) art punk-star. Thus with respect to the first painting, the Old woman selling eggs, by Hendrick Bloemaerts, Hirst comments that the egg that the woman holds in her hand is like a naked skull. In view of Jacob van Loo's Bacchant he seems reassured that "binge drinking isn't a new phenomenon", and Cornelis Saftleven had "too many magic mushrooms" when painting his Satire on the trial of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt. Or maybe he meant the statesman ... Anyway ...

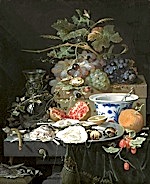

There was nevertheless at least one note that struck me as surprisingly

serious. It comes with an interesting selection of three fine, dark paintings

of dead game. Two of them are by Jan

Weenix, a third one is from the brushes of his father Jan

Baptist.

Here they are again, more or less as Hirst placed them in his selection-room at the Rijksmuseum, on the wall opposite and furthest from

the skull's shrine.

|

|

|

"The three paintings work like a kind of crucifixion triptych," Hirst comments.

"They are annoyingly accomplished painters, and underneath the physical

skill and beauty of the paint there's always a very dark & cruel view

of life [...]

The weak won't inherit the world."

...

Now here's what I would have liked:

I would have wanted to see that Love/God-skull outside of its fully darkened Ali Baba cave/shrine, and put out there in the light, surrounded by these 16 annotated paintings, with nothing but an additional spotlight from above, put in its glass cube on its pedestal, at, say, three-quarters of the room's length, closest to the wall with the Weenix triptych.

That's the way // uh-huh, uh-huh // I would have liked it.

...

Before leaving I decided to have a quick look at the Rijksmuseum´s most

famous painting, Rembrandt van Rijn´s Night

Watch.

You will find it just a short corridor away from the room with Hirst´s selection.

Viewers have to keep a certain distance from Rembrandt´s beroemde schuttersstuk,

a distance which is marked by a cord stretched between a couple of low metal

poles. Behind these, to the right and a bit in front of the painting, there

stands a uniformed guard. That is not so much to prevent anyone from stealing

the vast canvas, but rather to keep an eye open for art-vandals that

possibly might attack and attempt to damage the piece in some way.

Which

happened thrice over the last century.

...

It was sort of funny, really, to see the short and corpulent guard stand out there in the

dimmed light ... it did look to me as if he was a part of

the work, as if he had just come stepping out.

Very pomo.

I walked up to him and whispered: ¨Het lijkt wel of U net uit het doek

komt stappen, meneer!¨ He looked at me, puzzled. I don´t think he understood what I meant,

for he answered that indeed a number of slices, that together made up almost one-fifth of the original surface, were cut off the

linen in order to fit it between two doors. That was when in 1715 the painting was moved from the Kloveniersdoelen to

the Amsterdam town hall ...

The little fat guard standing there all alone next to that big painting... It would have made for another fine picture, but by then I knew one does not really appreciate photographs being taken in our Rijksmuseum.

I left it there.

...

[ For the Love of God, a copy of an original human skull cast in 2.156 grams of platinum encrusted with 1.106,18 carats of the finest quality ethically-sourced brilliant-cut diamonds, its forehead mounted with a magnificent internally flawless light fancy pink brilliant-cut pear-shaped diamond weighing 52,4 carats, surrounded by fourteen D flawless white brilliant-cut pear-shaped diamonds weighing a total of 37,81 carats and its jaws set with the teeth extracted from the original skull, will remain stealable from the first floor of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, until the 15th of december, 2008. ]

[ Next related SB-entry: Kings, Queens & Koons | Earlier related SB-entry: Jan Fabre @ the Louvre ]

notes __ ::

(*) That was around 10h. FPCM actually went there

even earlier on that same day, around 9h, when the museum just opened. Even

less visitors then. He told me workers still were vacuum-cleaning at the

time. [ ^ ]

tags: Amsterdam, postmodernism, postart, Rijksmuseum, diamonds

# .282.

del.icio.us | Digg it! | reddit | StumbleUpon

comments for Steal this for the love of god ... ::

|

Comments are disabled |